Battles:

"Battles are decisive"

Revolutionary Wars 1792-1795,

German Front 1796-1797,

Napoleon's First Italian Campaign 1796-1797,

Egyptian Campaign 1798-1801,

Second Italian (Marengo) Campaign 1800,

South German Campaign 1800,

Campaign against Austria 1805,

Campaign against Prussia 1806-1807,

Peninsular War 1807-1814,

Campaign against Austria 1809 ,

Russian Campaign 1812,

Spring Campaign in Saxony 1813,

Fall Campaign in Saxony 1813,

Winter Campaign in France 1814,

"Hundred Days" Campaign in Belgium 1815,

Valmy ,

Jemappes ,

Neerwinden ,

Wattignies ,

Fleurus ,

20 September 1792

|

French Army, the "Armee du Centre", under the elder General Kellerman

had maybe 52,000 men consisting of 35 battalions of infantry, 60 squadrons of cavalry,

and 40 guns. The French consisted of about one third regulars and two thirds

volunteers.

|

Prussian Army under the Duke of Brunswick with 34,000 men and 36 guns.

King Frederick William III was with the army.

|

|

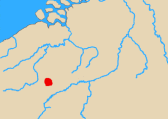

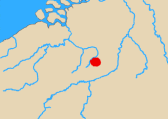

Valmy is about half way along the main road from Verdun to Rheims.

The Prussians had just taken Verdun and were moving on Paris.

The morning being foggy the Prussian didn't get formed up into

line and moving until 1:00 P.M. being stopped very shortly afterward

by French fire. A mutual cannonade continued until 4:00 P.M. when

heavy rain put an end to the battle.

The French casualties were about 300 men.

The Prussians lost 180 men killed and wounded.

Although Valmy was anything but a pitched battle it was nevertheless

extremely important. The Prussian advance which had looked to put an

end to the Revolution was halted and within a month Brunswick was

retreating to the Rhine.

|

6 November 1792

|

French Army of the North, under General Doumouriezwith 40,000

"hastily gathered and ill-disciplined" men.

|

Austrian Army, under Duke Albert of Saxe-Teschen with 14,000 men.

|

|

The Austrians were trained troops in an entrenched position at Jemappes west of Mons.

The French were poorly trained but in an enthusiastic attack took the position by storm.

The French certainly took heavy casualties but the exact numbers are unknown.

The Austrians lost about 5,000 men.

This was the first successful attack by French Revolutionary forces. It led to the

taking of Belgium (Brussels falling ten days later) and to Saxe-Teschen's

resignation.

|

18 March 1793

|

French Army of about 45,000 men, mostly raw recruits, under General Dumouriez.

|

Austrian Army of about 40,000 men. Main body under Prince Frederick of Saxe-Coburg.

Advance Guard led by Archduke Charles.

|

|

The French deployed on the 16th on some heights near Tirlemont about 35 km, or 23 miles, north-west

of Leige. The Austrians came up and deployed on the 17th. On the 18th the French attacked.

After fierce fighting in the center the French paused to reorganize around noon. However,

the Archduke Charles having won his battle to the north intervened bringing on a French

defeat.

The French lost about 4,000 men.

The Austrians lost about 2,000 men

This defeat shattered French morale and led to their abandoning their attack on

the Netherlands. The Austrians recovered Brussels.

Dumouriez defected to the Allies shortly afterwards.

|

15-16 October 1793

|

French Army of the North under General Jourdan with around 50,000 raw troops.

|

Austrian Army under Prince Frederick of Saxe-Coburg

with about 20,000 men,

several thousand more according to some sources at the battle. Maybe 14,000 maintaining the

seige of Maubeuge.

|

|

The French were moving on Maubeuge attempting to lift the seige there.

The Austrians deployed on a plateau near Wattignies village, about 10 km from Maubeuge,

in defense of the seige. Initial French attacks on the 15th were beaten off with

heavy loss.

Jourdan, however, redeployed about a fifth of his force during the night and on

the 16th succeeded in turning the Austrian left flank.

The French lost about 8,000 men.

The Austrians lost about 5,000 men.

The seige of Maubeuge was lifted. Critical because it was the last position

the Allies needed to take before being able to move on Paris. Jourdan got to

keep his head.

|

26 June 1794

|

French Army under General Jourdan with about 75,000 men.

|

Austrian Army under Prince Frederick of Saxe-Coburg with 52,000 Austrians and Germans.

|

|

This was a fight for Charleroi which the French took just before the battle commenced.

The Austrians advanced in several columns on the French redeployed in a defensive

ring with rough entrenchments. Although the central column under the Archduke Charles

did succeed in taking the village of Fleurus, there were further fortifications beyond

it and all the columns were finally beaten off by the French after some six hours of

fighting.

The French lost about 5,000 men, maybe more.

The Austrians likely lost about 5,000 men, but perhaps as few as 2,400.

Though essentially a tactical draw as a battle, Fleurus was a significant

strategic victory for the French. It resulted in the Austrians deciding to

abandon the theatre. As a result the Austrian Netherlands (modern Belgium)

fell to the French.

|

First Battle of Altenkirchen,

Ukerath ,

Kinzig ,

Rastatt ,

Ettlingen ,

Haslach ,

Forcheim ,

Neresheim ,

Friedberg ,

Amberg ,

Wurzberg ,

Biberach ,

Emmendlingen ,

Schliengen ,

Second Battle of Altenkirchen ,

Diersham ,

4 June 1796

|

French Army of the Meuse and Sambre commanded by General Jourdan

Actual forces engaged were its Northern wing led by General Kleber with around 22,000 men.

|

Left wing of Austrian Army of the Lower Rhine under Prince Wurttemburg with about 24,000 men.

|

|

The French with three divisions, the center under Lefebvre, Soult on the right, and Ney on left, had

already manouvered the Austrians off the line of the Seig, and out of a position at Ukerath since

the beginning of the month.

The Austrians tried to hold at Altenkirchen but after hard fight were pushed out.

The French losses are unknown but are unlikely to have been great.

The Austrians lost about 1,500 men and 12 guns.

The French pursued the retreating Austrians vigorously; pushing them back to line of the Lahn river 50 km to

the south. The battle also led to their capturing vital Austrian magazines with badly needed supplies.

|

19 June 1796

|

Rearguard of the French Army of the Meuse and Sambre with around 22,000 men, General Kleber commanding.

|

Advance guard Austrian Army of the Lower Rhine under General Kray with about 13,000 men.

|

|

The Archduke Charles of Austria having marched with reinforcements to the support of the Austrian

Army of the Lower Rhine, Prince Wurtemburg commanding, the fortunes of war turned against

General Jourdan commanding the French Army of the Sambre and Muese.

Forced back from the line of the Lahn the French were in full retreat when General Kleber commanding

their rearguard decided to turn and give the Austrian advance guard under Kray which he

significantly outnumbered a lesson.

As it happened it it was the normally very capable Kleber that received the lesson.

He learned that Austrian troops could indeed fight very hard and that in the pursuit the

Austrian superiority in cavalry was something to be feared.

The French lost about 1,500 men killed or wounded and another 700 taken prisoner.

The Austrians lost 500 to 600 men killed or wounded.

The battle was undoubtly a caution to the French generals and a help to Austrian morale. Unfortunately

for the Austrians, Bonapartes successes in Italy had led to half their Army of the Upper Rhine being

being sent there. This significantly weakened the Austrian position along the southern portions of

the Rhine and General Moreau commanding the opposing French Army of the Rhine and Mosselle was not

slow to take advantage.

The Archduke Charles and the some 25,000 troops he commanded had to hurry south. The situation in

the north reverted back into favoring the French.

|

28 June 1796

|

The French Army of the Rhine and Moselle under General Moreau, actually engaged was the

column commanded by General Desaix with around 34,000 men.

|

The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine commanded by General (FML) Latour,

forward elements actually engaged commanded by General Sztarry numbered about

17,000 men.

|

|

The French under Moreau had stolen a few marchs on the already outnumbered Austrians

under Latour, and managed to take a bridgehead across the Rhine opposite Strasbourg at

Kehl by stealth and daring.

The Austrians fighting in the terriority of wavering allies held a strong position along

the Kinzig River and

so decided to try and hold out until reinforcements arrived despite being heavily outnumbered.

In the event the Austrians were unable to hold and had to fall back

The French losses are unknown

The Austrians lost about 1,800 men.

The Austrians lost what little hope they had of containing the French bridgehead.

A bad situation had become worse.

|

5 July 1796

|

The French Army of the Rhine and Moselle with around 34,000 men engaged, General Moreau commanding.

|

Forward elements of the Austrian Army of the Lower Rhine under General Latour with about 18,000 men.

|

|

Having failed to hold the line of the river Kinzig the Austrian forces retreated a little north to

the line of the River Murg. Rastatt was one of the main positions on this line. The Austrians

actually managed to hold there, but not elsewhere. Once again they were forced back.

Both sides lost about 500 men

Despite their numerical inferiority the Austrians had hoped the terrain and being on the defence

might allow them to hold the French up long enough for reinforcements to arrive.

Against an opponent other than a French Revolutionary army commanded by General Moreau this might

have worked.

|

9 July 1796

|

The French Army of the Rhine and Moselle with around 65,000 men engaged, General Moreau commanding.

The columns of both Desaix and St. Cyr were present.

|

The Austrian Army of the Lower Rhine with reinforcments around 40,000 men, about half cavalry,

the Archduke Charles commanding.

|

|

The Archduke Charles having reinforced General Latour's Army of the Upper Rhine the Austrian's

once again attempt to stop the advance of the French under General Moreau.

They faced two of the three "columns" making up the Army of the Rhine and Moselle. That of

Desaix attacked in the center around the village of Malsch. Here the fighting was bloody

but the Austrians held.

The column under St.Cyr attacked the Austrian left and the Austrians were pushed back.

The French lost about 2,000 men.

The Austrians also lost about 2,000 men, half of them prisoners.

Tactically a draw, stategically the battle was a loss for the Austrians. Charles needed to have

defeated Moreau decisively. His line of communications ran east back through

Stuttgart and along the Danube to Austria.

It was threatened locally by the French movement on his left, in his deep rear

to the north it was threatened by the advance of Jourdan's army, and to the south

in the Black Forest it was threatened by the successes of Moreau's

third column under General Frolich.

On July 12th Charles ordered garrisons into forts intended to deny the French

a secure line of communications and fell back on his own.

|

14 July 1796

|

General Ferino's column of the French Army of the Rhine and Moselle with likely with somewhere

around 20,000 men.

|

A mostly German Allied force under General Frolich with about 15,000 men,

strong in cavalry.

|

|

General Frolich's Allied force deployed between Kinzig and Elz tried to deny passage of the

Black forest to the French column under General Ferino.

The French succeed in pushing in the Allied center around Haslach and the flanking

Allied forces were forced to retreat.

Losses are unknown, but not likely high as only the center was engaged.

The French sucess in the Black Forest created yet another threat to the Austrian lines

of communication. Frolich and the other Austrian commanders in the south began

to fall back on Danube hoping to concentrate on the Danube along with the forces

of Archduke Charles. The territory of the small south German states was abandoned.

|

7 August 1796

|

The French Army of the Sambre and Meuse with around 46,000 men engaged,

General Kleber commanding, as Jourdan was ill.

|

The Austrian Army of the Lower Rhine with 40,000 men,

General Wartensleben commanding.

|

|

Given the fort of Forcheim, a defensible river line and the fact that the more numerous French had been

forced to make detachments to defend their communications, an Austrian stand seemed possible.

Kleber, acting as General-in-Chief, sent Lebefvre's division to attack the Austrian right. He sent

Bernadotte's and Championnet's divisions to attack the Austrian right.

He sent Collaud's division against Forcheim in the center. Ney's regiment of this division

suceeded in taking Forcheim, which as well as forcing the Austrian's to retire earned Ney

promotion to Brigadier General.

Losses unknown, French claim to have taken 60 cannon and "many other munitions" in Forcheim.

The Austrians under Wartensleben were forced to continue their withdrawal south and east.

|

11 August 1796

|

The French Army of the Rhine and Moselle with around 50,000 men engaged,

General Moreau commanding.

|

The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine with about 55,000 men,

the Archduke Charles commanding.

|

|

Having concentrated all his forces from the upper and middle Rhine, and with the French spread out

and depleted by detachments the Archduke decided to turn and fight.

His plan was one of multiple converging columns. In the event, whether because the plan was too

complex or because of driving rain and muddy roads, the attack was poorly co-ordinated.

The French left gave way but their center and right held.

The Archduke disengaged and withdrew before Moreau could counter attack.

The French lost about 2,400 men.

The Austrians also lost about 1,600 men.

This battle is variously described as a French victory, a draw, or an Austrian victory.

Certainly if the Archduke's intent was to defeat Moreau decisively he failed. If he only wished to

give Moreau sufficient pause that he could disengage, join Wartensleben's forces and fall on Jourdan's

army (which is what happened in the event) then he succeeded.

Most likely he hoped to defeat Moreau decisively, but failing that he put the draw he actually achieved

to good use.

|

24 August 1796

|

The French Army of the Rhine and Moselle with around 53,000 men engaged,

General Moreau commanding.

|

The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine with about 34,000 men,

General Latour commanding.

|

|

General Latour attempted yet another corden defense running the length of the Lech river with its

center at Friedberg just east of Augsberg.

Despite the strong position and the Lech being swollen with the run off from recent rains, French

initiative and numbers made themselves felt and the Austrian center at Friedberg was smashed with

considerable loss to the units immediately involved.

Latour was forced to fall back towards Munich and the Isar.

The French likely lost a few hundred men, some drowned in the crossing of the Lech.

Unfortunately, and as usual, the only public reports of the action were French, and, as usual,

they mentioned enemy losses but not their own.

The Austrians lost about 1,700 men and 16 cannons.

Although tactically Moreau won yet another French victory, strategically Friedberg was a mistake on

his part. He was plunging deeper into Bavaria as the Archduke was defeating Jourdan to the north,

and would continue to do so even as the Austrians hounded the Army of the Sambre and Meuse close

to destruction.

|

24 August 1796

|

The French Army of the Sambre and Meuse with around 45,000 men,

General Jourdan commanding.

|

The Austrian Army of the Lower Rhine plus reinforcements with about 63,000 men,

the Archduke Charles commanding.

|

|

The Archduke fell on Jourdan's right flank and rear as Wartensleben's Army attacked from the front.

Now outnumbered and in a false position Jourdan fell back north and then west on poorer secondary

roads.

Ney showed, for perhaps the first time, the brilliance in rear-guard actions that he later displayed in

Portugal and Russia. The French Army although defeated and involved in a costly retreat did not

disintegrate, and was not trapped.

The French lost about 4,000 men.

The Austrians also lost about 4,000 men.

Amberg and the subsequent Austrian pursuit of Jourdan completely reversed the strategic situation

in Germany.

It was a bold and timely move by a commander that had up to that time been underestimated.

|

3 September 1796

|

The French Army of the Sambre and Meuse with around 40,000 men engaged,

General Jourdan commanding.

|

The Austrian Army of the Lower Rhine with reinforcements for about 44,000 men,

the Archduke Charles commanding.

|

|

An Austrian column under General Hotze beat the French to Wurzberg. The rest of the Archduke's

army was in close pursuit. The Austrian superiourity in cavalry and light troops, as well as

the fury of the local population at French depredations was telling on the French Army

Jourdan decided to make a stand on the heights on the right bank of Main running between

Wurzberg and Schweinfurt.

In the event he was unable to keep the Austrian columns from crossing the river and

eventually after hard fighting prevailing along his entire front.

The French army was routed.

The French lost about 2,000 men and 7 guns. Graham reports 3,000 taken prisoner

The Austrians lost about 800 men.

Wurzberg sealed the results of Amberg. The French Army of the Sambre and Meuse in Franconia was

defeated and was driven back to its starting positions of the early summer with heavy losses.

Furthermore it was so disorganized as to pose no further threat. Moreau would have to face the

Archduke on his own.

|

2 October 1796

|

The French Army of the Rhine and Moselle with around 40,000 men engaged,

General Moreau commanding.

|

The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine with about 23,000 men,

General Latour commanding.

|

|

Moreau's French Army of the Rhine and Moselle was forced to retreat by the Archduke's successes in the North

against Jourdan's Army of the Sambre and Meuse.

Latour's Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine followed.

Near Biberach on the River Riss in the valley of the upper Danube, Moreau decided to pause and

attack Latour so as to gain breathing room.

The French counter-attack was entirely successful, Desaix's column in particular managed to

overwhelm a weak Austrian right wing and penetrate into Biberach itself.

Latour successfully disengaged the rest of his forces by evening.

The French losses seem to have been minimal.

The Austrians lost about 4,000 men, many prisoners, and 18 guns.

Although still threatened by minor Austrian forces, a peasant uprising, and the Archduke on his

northern flank, Moreau had managed to discourage a close pursuit by Latour and gain manouvering room.

|

19 October 1796

|

The French Army of the Rhine and Moselle with around 45,000 men engaged,

General Moreau commanding

|

The Austrian Army with about 35,000 men,

Archduke Charles commanding.

|

|

Moreau's French Army of the Rhine and Moselle had sucessfully avoided being cut off, but now

faced the majority of the Austrian forces in Germany united under the command of Archduke Charles.

Moreau took up defensive positions along the Elz river. The Austrians succeeded in taking

Emmendlingen in his center and Waldkirch on his right. Moreau defeated, withdrew in the evening.

The French lost around 2,000 men.

The Austrians losses were likely significant, as the narratives have them engaged along a

broad front and the French fighting hard, unfortunately I've not yet found any numbers.

A guess would be 900 to 1200 men. Graham in fact gives French losses as 2,000 prisoners

"and a like number killed and wounded." and goes on to write "The lost of the Austrians was

not the fourth of it."

Moreau was forced to fall back 40km south to Schliengen where he deployed in defence of the

French bridgehead at Hunningen.

The Archduke had succeeded in pushing the French out of all but a small slice of Germany.

|

23 October 1796

|

The French Army of the Rhine and Moselle with around 30,000 men engaged,

General Moreau commanding.

|

The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine with about 40,000 men,

Archduke Charles commanding.

|

|

Moreau having sent Desaix across the Rhine and the Austrians having received some reinforments

from the blockade of Kehl, the Archduke Charles had the advantage of numbers for change.

The French, though, were defending and in an excellant position for it.

The Austrians attacked all along the line and pushed the French back along all of it without

making any decisive breakthroughs.

Moreau withdrew during the night.

The French losses seem to have been minimal.

The Austrians lost about 800 men.

The Austrians and French both have monuments claiming Schliengen as a victory.

The French because they were able to withdraw and cross the Rhine without Moreau's army being destroyed.

The Austrians because they were able to force the French into withdrawing across Rhine.

Tactically the side who pocesses the battlefield would normally seem to be the winner.

However, strategically the Archduke had failed to destroy the French, or take their bridgeheads at

Huningen and Kehl. If he had succeeded in this the Aulic Council in Vienna might have been

willing to let him go to Italy with significant numbers of veteran troops.

Napoleon's famous victories in Italy during late 1796 and early 1797 were close run

affairs as it was. Faced with the Archduke and more and better Austrian troops

he may not have won those victories at all. The history books would now read

very differently.

|

18 April 1797

|

The French Army of the Sambre and Meuse with around 70,000 men engaged,

General Hoche commanding.

|

The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine with about 40,000 men,

General Werneck commanding.

|

|

Hoche crossed at both Dusseldorf and Neuwied. He caught Werneck still in the process of

concentrating his troops who'd been spread out in a cordon defence.

Werneck fell back to Lahn.

The French losses were likely minimal.

The Austrians lost about 5,000 men and 27 guns.

The Austrians had been pursued to the gates of Frankfurt when operations were halted on news

of peace negotiations.

|

20 April 1797

|

The French Army of the Rhine and Moselle with around 60,000 men,

General Moreau commanding.

|

The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine with about 17,000 men,

General Sztarray commanding.

|

|

Moreau managed to get his advance divisions under Vandammne and Davout across the Rhine in boats.

By the time Sztarray counterattacked sufficient reinforcements had crossed via a pontoon

bridge to hold him off.

The French losses were about 3,000 men.

The Austrians lost about 3,000 men in casualties, and a further 3,000 in prisoners.

In addition to recrossing in the Rhine successfully and establishing himself in superior force,

Moreau managed to re-take the bridgehead at Kehl. If hostilities hadn't been halted by

peace talks it likely would have not gone well with the Austrians.

|

Montenotte ,

Millesimo ,

Dego ,

Ceva ,

Mondovi ,

Fombio ,

Lodi ,

Borghetto ,

Lonato ,

Castiglione ,

Roveredo ,

Bassano ,

Caldiero ,

Arcola ,

Rivoli ,

12 April 1796

|

French Army of Italy under Napoleon, then

simply General Bonaparte, with 9,000 men mainly belonging to LaHarpe's division.

Massena led one of LaHarpes's brigades on the decisive

flanking attack while LaHarpe himself conducted the pinning frontal assault.

|

Allied Austrian-Piedmontese Army represented by the Austrian division of General (FML) Argenteau with 6,000 men.

|

|

Argenteau's forces had been pushing back a small French brigade under Rampon throughout the days of April the 10th and 11th.

This was part of a rather ill co-ordinated Austro-Sardinian offensive against Savona and Genoa.

On the 12th the French counter-attacked. LaHarpe's brigade joined Rampon's and did so frontally.

While the Austrians were engaged in defending against this Messena's force flanked them on their rear right.

Given how the mountainous terrain channeled movement and communications the Austrians stood in danger of being totally cut

off.

Their force disintegrated trying to withdraw.

The French casualties were likely about 120 men. Messena's force being known to have lost about 50 men

The Allies lost 700 men killed, wounded, and (mostly) missing according to Austrian official returns

although Napoleon claimed 3,000, and several modern authorities give 2,500. Regardless, more importantly, according to

Argenteau's own account his force was effectively destroyed at the end of the day. His men were exhausted and scattered.

He was left with only 700 disorganized men under his direct control.

Napoleon had identified a low pass running west and slightly north from the area of Savona through Millesimo and Ceva to the area of Mondovi as the primary

route he needed to open for his Army to able to establish itself in the plains of Northern Italy. Montenotte lay north of this

route's eastern end. Stalling the Austrian threat in this area so he could fall upon the Sardinians under Colli was a necessary

first step in his plans.

So although the actual losses in this series of hard fought but small skirmishs are uncertain and likely not that high, the

undeniable disorganization of the Austrians was a critical precondition to Napoleon's final success.

|

13 April 1796

|

French Army of Italy under Napoleon,

forces under General Augereau with two demi-brigades

and Joubert's brigade, about 10,000 men in all, were engaged.

|

Allied Austrian-Piedmontese Army under General Colli, his leftmost Austrian provisional Corps under

Provera with about 2,500 men was engaged.

|

|

The main French attack came on the 13th. The plan had been that it would be spearheaded by Augereau's division

attacking through Carcare from the south and then east along the Savona-Ceva road to Millesimo. As it happened

Carcare was occupied without resistance on the evening of the 12th, but Augereau's main force then got held

up by the castle of Cassario on the 13th. The Sardinians had hastily thrown a picked force of men into it after the Austrian

set-backs of the 12th.

While the French main force made fruitless and costly attacks upon Cassario, a demi-brigade of Augereau's commanded by

Menard by-passed the castle and drove the Sardinians out of Millesimo. Being the day's only French success this is

what made its way into Napoleon's reports and the history books.

The Allied force in Cassario, surrounded and short of supplies, finally surrendered on the morning of the 14th.

The French casualties were likely about 1,200 men, at least 600 at Cassario.

The Allies likely lost about 1,200 men, at least 800 at Cassario

Although it put a days delay into French plans and a dent into their morale the isolated bravery of the

defenders at Cassario failed to affect the campaign's course. By the morning of the 14th the French were

solidly in place to continue their attack against either the Austrians in Dego or the Sardinians at

Montezemolo. Montezemolo which is between Millesimo and Ceva is the highest point in the road between Savona

and Ceva which Napoleon was seeking to capture. Dego was a vital point on the main line of communications between the Austrian and

Sardinian armies.

|

14-15 April 1796

|

French Army of Italy under Napoleon, the 8,500 men of

Messena's division were directly engaged initially. Later joined

by perhaps 8,000 men of LaHarpe's division.

|

Allied Austrian-Piedmontese Army under General Argenteau and Colonels Avogadro and

Vukassovich with about 8,000 men.

|

|

Massena attacked Dego on the morning of the 14th with another of his frontal pinning attacks combined

with a flanking maneuver. He took the position rather easily at a cost of about 200 French dead.

The Austrian defending force had about twice as many dead and thousands of them were taken prisoner.

Both the original 4,000 defenders of Dego under Colonel Avogadro and a relief column under General Argenteau

were caught up in the Austrian rout.

At nightfall on the 14th while their cavalry pursued the defeated Austrians the poorly supplied French soldiers dispersed

to forage and loot.

Early the next morning a force of some 3,000 plus Austrians under Colonel Vukassovich surprised the unwary

French routing them in their turn, taking many of them prisoner.

However, by the middle of the 15th Messena and a furious Napoleon were staging yet another counter-attack with both Massena's

own troops and

those of LaHarpe's division. Despite inflicting severe casualities of about 1000 men upon the French Vukassovich

was forced out of Dego. He managed to extricate only a small fraction of his men from the defeat.

The French casualties were somewhere between 1000 and 2000 men, 200 to 400 dead.

The Allies lost 4000 to 6000 men, upwards of 400 dead, but most taken prisoner

Once again the initiative of individual Allied commanders and the bravery of their men was

wasted due to ineffective overall command. The French may have been deeply disturbed by events

at Dego and Napoleon temporarily induced to greater caution, but stategically Napoleon had

succeeded in separating the Austrian and Sardinian armies from each other. He was now free to

fall upon the Sardinians under Colli without fear of Austrian interference.

|

16-17 April 1796

|

French Army of Italy under Napoleon, then

simply General Bonaparte, with 24,000 men. Generals Augereau

and Serurier commanded the main two divisions engaged.

|

Allied Austrian-Piedmontese Army under General Colli with 13,000 men.

|

|

Ceva was a fortified location the taking of which had figured largely in Napoleon's planning from the beginning of

the campaign.

Augereau's forces suffered about 150 casualities in an unsuccessful assault they made on the 16th.

The next day they tried again

this time in conjunction with the 9,000 men of Serurier's division coming up from the south.

Colli had already withdrawn the night before. He'd feared being outflanked by Serurier.

The French found that only a garrision in the fortress remained. They occupied

the town and surrounding fortifications without opposition.

Morever although the fortress garrison refused to surrender

it did not harass the main body of French troops that Napoleon ordered to bypass it.

The French casualties were likely about 750 men.

The Allies probably lost about 350 men in actual battle,

but more (up to several thousand) from desertion and straggling

How to take the excellent defensive position at Ceva had been a major concern of Napoleons.

Having mostly neutralized it without having to bring up artillery and making a setpiece attack

was a major stroke of good fortune. It also let Napoleon shorten his extremely

overstretched supply lines as the route to Ceva from the south was much shorter than that through

Savona. Still the French supply situation remained very bad and Napoleon needed to break through to

the wealthy plains of Northern Italy quickly before his army disintegrated.

|

21 April 1796

|

French Army of Italy under Napoleon, then

simply General Bonaparte, with 23,000 men

|

Allied Austrian-Piedmontese Army under General Colli with 9,000 men.

|

|

After his withdrawal from Ceva Colli had taken up positions at San Michele several miles east of Mondovi.

This excellant defensive position was covered by the Tanaro river in the north and the Corsaglia river to the south.

On the morning of the 19th Serurier attacked in the south and Augereau in the north. Without artillery support they

took heavy losses and their hungry and undisciplined troops gave up their few gains to Sardinian counter-attacks.

The French spent the 20th re-grouping. The Sardinians spent the day assessing their situation and found they

didn't like it. The Austrians under Beaulieu having regrouped to the north-east and French troops on their

left under Masssena threatening their communications with Turin they decided to withdraw once more.

Destroying the bridges over the Corsaglia they started withdrawing on the night of the 20th.

This time Napoleon did not let them get away. He defeated their rearguard during the night and entered the town of Mondovi

early on the 21st as Colli's army retreated in disorder.

The French casualties were likely about 700 men.

The Sardinians lost about 400 men

As usual in this part of the campaign losses through desertion and straggling dwarfed actual casualities,

both sides suffering badly from poor supplies, bad weather and difficult terrain.

With the capture of Mondovi the path to the plains of Northern Italy lay open.

Of more immediate importance vast supplies of food and equipment the French Army desperately needed

were captured intact. The Sardinian army was a shambles and they'd begun negotiations for a

separate peace.

|

8 May 1796

|

French Army of Italy under Napoleon, then

simply General Bonaparte, with 12,000 men actually engaged consisting of an Advance-Guard under General Dallemagne

supported by LaHarpe's division.

|

Austrian Army of North Italy under General Beaulieu.

Left wing detachment of General Liptay with 5,000 men defending, 4,000 of them infantry, 1,000 cavalry.

|

|

After extracting his army from Piedmont, the Austrian general Beaulieu set up a cordon defence of Lombardy behind the flood swollen

Po River. He destroyed all the bridges across it. This made any direct frontal attack by the French problematic, but it also

meant the Austrians were in turn unable to easily interfere with French movements.

Napoleon exploited this by rapidly marching across the Austrian front to their far left wing and crossing at Piacenza on May 7th.

The Austrian force under Liptay that Beaulieu had dispatched to oppose this crossing arrived too late.

Instead reaching the village of Fombio north of the Po near Piacenza it stopped and dug in to await

the French attack. This attack came early on the 8th. By the evening, after heavy fighting the forces under Liptay

had been pushed out of Fombio. They retreated north through the town of Codogno and to the crossing of the Adda River at Pizzighettone.

The French took Codogno but almost lost it again when a column from the Austrian main army stumbled across them during the night.

LaHarpe, the senior French general on the scene, was killed amid the confusion.

The French loss of momentum allowed the Austrian Army to escape intact.

The French casualties were more than 450 men, at least 150 killed.

The Austrians lost close to 1000 men, mostly prisoners

The actions of Fombio/Codogno sealed the success of Napoleon's crossing at Piacenza and doomed the Austrian defence of the

Duchy of Milan. However, they also put paid to Napoleon's hope of either trapping the Austrian Army or at least forcing

it to retreat north and away from its eminently defensible base at Mantua.

|

10 May 1796

|

French Army of Italy under Napoleon, then

simply General Bonaparte, with about 15,000 men. Advance-Guard under Dallemagne later

supported by Massena's and Augereau's divisions.

|

Rearguard of Austrian Army under General Sebottendorf with 10,000 men total.

|

|

The bulk of the Austrian Army had got across the Adda River on the 9th, but the French caught up with

its rearguard under General Sebottendorf at the Lodi crossing on the 10th. They took the town itself

without difficulty in the morning but the bridge across the Adda was better defended.

Most of the day passed in an artillery duel as the French brought up more guns and men.

Finally around six the Advanced-Guard of 3,500 picked men stormed across the bridge with the

encouragement of many higher ranking officiers including Lannes, Dallemagne, Messena and Berthier. Napoleon

had taken a hand in the laying of the supporting cannon. The first line of Austrians broke and fled.

Faced with the deploying divisions of Augereau and Messena as well as the Advance-Guard the

Austrian rearguard as a whole made an orderly retreat. Apparently the French were too exhausted or it

was too late for them to vigorously pursue the Austrians.

The French casualties were at least 500 men, and likely closer to 2000.

The Austrians lost about 2100 men

Lodi was a French tactical victory. It may have had wider repercussions by cementing the relationship between the

leadership of the French Army of Italy and their troops. However, any hope Napoleon may have had of catching a

retreating Austrian Army and destroying it with a vigorous pursuit were dashed. The Austrians had got away to

fight another day, and would have time to properly garrison Mantua. The French Army took several weeks in which

it occupied Milan, got some deserved rest, and received its first pay in years.

|

30 May 1796

|

French Army of Italy under Napoleon, then

simply General Bonaparte, with 28,000 men

|

Austrian Army under General Beaulieu with 19,000 men.

|

|

After evacuating Lombardy Beaulieu reinforced the garrison of Mantua to the fortress' full capacity of over 12,000 men.

The remainder of his Army he used to form another cordon defence, this time behind the river Mincio.

The Mincio runs from Lake Garda and past Mantua before reaching the Po. There were four bridges across the Mincio

at Peschiera, Borghetto, Goita and Rivalta.

Napoleon carefully designed his approach manoeuvres so as to

confuse the Austrians as to which of these he intended to take.

He launched Augereau at Peschiera in a major diversionary attack.

This may have been wasted effort, as Beaulieu was sick and

the Austrian command riven with dissent.

In any case, when the advance guard of picked men under

General Kilmaine stormed the crossing at Borghetto they quickly took it despite

sharp resistance by the small Austrian force there.

Supporting units beat off the limited Austrian counter attacks and fanned out east of the crossing thereby splitting Beaulieu's field army in half.

The French casualties were at least 100 men likely about 150 men total.

The Austrians lost roughly 600 men

His field force dismembered Beaulieu retreated up the Adige river valley towards Trento.

Napoleon now held Northern Italy with the exception of Mantua. The remainder of

the campaign would consist of his beating off attempts by successive Austrian armies to relieve

the besieged garrison there.

|

31st July to 5th August 1796

|

French Army of Italy under Napoleon, then

simply General Bonaparte, actually engaged piecemeal by brigades were the divisions of Despinoy

with 4,000 men.

and Massena with maybe 11,000 men around Lonato

itself. For particular periods Augereau's division also participated in the battles against the Austrian Western column.

Serurier's division gave up two brigades, one each to reinforce

Augereau's and Massena's divisions. The smaller divisions of Kilmaine and Sauret, about 5,000 men each,

also played a role in defeating Quosdanovich's forces. Both of these gentleman fell ill during the campaign and their units

were temporarily commanded by Beaumont and Guieu respectively.

So in summary starting with a weak division of about 4,000 men the French reinforced until

almost their whole army,

something in excess of 30,000 men, was concentrated against Quosdanovich.

|

Austrian Forces western column under General Quosdanovich with about 17,500 men.

Quosdanovich's force was divided into two advance-guards and 4 brigades. The advance guards seem

to have had about 1,800 men each and the brigades roughly 3,500 men each. Much of the hottest action

around Lonato involved Ott's and Ocskay's brigades.

|

|

The week's action in which Napoleon first stopped and then forced back the Austrian western column under

Quosdanovich was a chaotic dogfight of which the two actions at Lonato were only a representative part.

The first of these actions took place on July 31st between Ott's brigade in Lonato and Despinoy with about 4,500 men

who succeeded after a hard fought action in forcing Ott back.

The second action was on August 3rd in which Massena with about 11,000 men managed to throughly maul the much

out-numbered brigade under Osckay.

Overall the situation went from one in which Quosdanovich with the advantages of superior numbers and surprise had

managed to sever the French main line of communications, and Napoleon was seriously considering retreat to Lombardy,

to one where Quosdanovich was retreating north having lost half his men.

Part of the reason for this was a fatal Austrian inability to co-ordinate their various forces, both the main

columns and the brigades within them. But Napoleon's decisive willingness to abandon the seige of Mantua, and

by harsh forced marchs combine his whole army sucessively against the separate columns of Austrians was also key.

The French casualties were likely about 5,000 men over the week.

The Austrians lost about 7,000 men in the same period

Quosdanvich's threat to French communications was beat off and his forces prevented from combining with or

even indirectly aiding the main column under Wurmser. The price the French paid was having to lift the seige

of Mantua and losing their seige train in the bargain.

|

5 August 1796

|

French Army of Italy under Napoleon

with about 33,000 men.

|

Austrian main army under General Wurmser

with about 25,000 men.

|

|

Having driven off Quosdanovich's Western column Napoleon now assembled his entire army in opposition

to the Austrian main force under Wurmser.

Napoleon began the battle slightly outnumbered facing Wurmser to the south-east of Castiglione with the

divisions of Massena and

Augereau, as well as his cavalry for a total of about 21,000 men.

His plan was to engage and hold Wurmser with this main force and then with reinforcing forces first

defeat and then destroy the Austrian Army.

In the event the plan didn't quite work.

An initial feigned withdrawal by Messena and Augereau drew the Austrians forward as intended, but

attacks by Despinoy's division arriving from the north-west on the French left, and by Marmont with

a picked assault party and force of horse artillery on the Austrians key position facing the French

right, both met with insufficent success. They pushed the Austrians back but they did not break them

and they did not force the commitment of all the Austrian reserves.

The attack by Sururier's division (temporarily under Fiorella) coming up from the south-east was made

early. Although tactically sucessful it failed in its objective of trapping a completely crushed

Austrian Army.

Wurmser's forces fighting hard were mostly able to retreat in moderately good order to the north-east

aided by a sortie by a force under Bajatich left behind to guard the crossings of the Mincio at

Peschiera.

In addition to their timing and co-ordination problems the French troops were simply too exhausted

from the hard campaigning of the last week to be able to pursue their advantage.

The French casualties were about 1,500 men.

The Austrians lost about 3,000 men; 2,000 killed or wounded, and 1,000 prisoners, as well as 20 guns.

Having defeated the main Austrian Army Napoleon was able to drive it back into the Tyrol and resume

a blockade of Mantua. Since he had lost his carefully assembled seige train a full seige was no longer possible.

|

4 September 1796

|

French Army of Italy under General Bonaparte

. Actual battle fought by Massena's division with about 10,200 men.

Divisions of Augereau (10,100 men) and Vaubois (5,445 men)

plus brigade under Guien (2,775 men) in support.

|

Austrian main army under General Wurmser.

Actual battle fought by portion of General Davidovich's wing (25,000 men) of about 14,000 men in strength.

|

|

The major engagement in the opening phase of the autumn portion of the 1796 Italian campaign. Napoleon was

under orders to take the offensive against the Austrians, and for his part Wurmser was making the second

Austrian attempt to relieve Mantua.

Wurmser led off by advancing down the Brenta river valley with 20,000 thousand of his 45,000 men. The idea was

to meet Bonaparte in the plains around Verona rather in the mountainous Adige river valley.

He left 25,000 men under General Davidovich to defend Trent and his supply lines. More than enough he believed given the

mountainous terrain.

Wurmser and the Austrians were very mistaken about this. Although the formidable terrain had the potential to allow small

numbers of men to hold up much larger bodies troops it also greatly amplified the effects of the greater cohesion and

speed of French command, and those of the superiour morale and initiative of the French troops.

As in the spring small bodies of Austrians faced locally more numerous French forces who attacked them

vigorously in the front while at the same time other French forces turned their flank. They rarely managed to

hold or retreat in good order.

And so it was just south of Roveredo on the morning of September 4th. The Austrians fought hard against

Massena's forces, but Vaubois forces threatened to flank them from the west and Augereau's from the east.

Once the retreat began the Austrians proved unable to reform a defense despite very favorable terrain.

The French pursuit continued until they took the vital city of Trent some days later.

The French casualties were a few hundred men.

The Austrians lost about 6,000 men; mostly prisoners, as well as 20 guns.

The French shattered half the Austrian army and secured the Adige river valley for both defensive

and offensive purposes. They were securely in the Austrian rear having cut their previous supply lines

although the Austrians could potentially draw supplies from the east. Napoleon had the choice of

moving down the Adige Valley to defend in the Verona area or of advancing down the Brenta valley in

an effort to take Wurmser's force in the rear.

|

8 September 1796

|

French Army of Italy under General Bonaparte

using divisions of Massena and

Augereau with about 22,000 men in all.

|

Austrian main army under General Wurmser with

about 20,000 men.

|

|

The French Army of Italy pursued the Austrians under Wurmser down the Brenta Valley towards Bassano

overwhelming the rearguards of a few thousand men Wurmser had left behind to delay them.

Very early on the 8th of September, with Massena's division on west side of the Brenta River and Augereau's

on the east side, the French caught up with the two rear 'divisions' of the Austrian Army commanded by

Quasadanovich and Sebottendorf near Bassano. The Austrians were not ready. Their supply trains were

blocking the streets of the town and they had at most 14,000 men available, perhaps no more than 7,000.

Whatever the case they were quickly defeated with heavy losses, the survivors split and scattered.

Their supply train fell into French hands.

Wurmser, however, was able to rally a significant number of survivors plus the forces of his

leading division under Meszaros into a body of 10 to 12 thousand men and lead them on a daring march

into Mantua.

The French casualties were a few hundred men.

The Austrians lost about 4,000 men, 35 guns, and 2 pontoon bridges.

Bassano marked the the defeat of the second Austrian attempt to relieve Mantua. It came

very close to resulting in the total destruction of the main Austrian field army in Italy.

In the event, the main surviving fragment of that army and its commander were bottled up in

Mantua. Disease was rampant and supplies short there so its strength began to rapidly waste away.

In practical if not moral effect the Austrians might as well as been killed or taken prisoner.

The Austrian authorities would need to find yet another army somewhere.

|

12 November 1796

|

French Army of Italy under General Bonaparte

using divisions of Massena and

Augereau; about 13,000 men.

|

Austrian army under General Alvintzy with

about 18,000 men actually engaged.

|

|

The Austrian army under Alvintzy was advancing from Bassano to Verona in its third effort to

relieve Mantua. Alvintzy pushed his advance guard (8,000 men) under Hohenzollern out ahead to

the Caldiero ridge. Bonaparte determined to attack it with the divisions of Massena and Augureau.

The French march to the attack was delayed by icy weather and was effectively held by the Austrian Advance

Guard long enough for their main body to come to their aid. The French were forced to fall back

with heavy loses for no gain.

The French casualties were in the area of 2,000 men.

The Austrians lost about 1,200 men.

Caldiero was perhaps the first clear defeat the French Army of Italy suffered under Bonoparte.

Already exhausted from almost a year's hard campaigning against successive Austrian armies the

morale of the French troops took a significant hit. Furthermore, Bonaparte faced an Austrian army at

the gates of Verona against which victory in a head-on fight looked unlikely.

|

15-17 November 1796

|

French Army of Italy under General Bonaparte

mainly using the divisions of Massena and

Augereau but with detachments from other

formations for a total of about 19,000 men in all.

|

Austrian main army under General Alvintzy with

about 24,000 men total.

|

|

Having failed to defeat Alvintzy's army on its approach march Bonaparte was left facing

a new more numerous Austrian army before Verona in terrain that favoured Austrian

tactics. Morever his troops were tired and their leadership decimated by constant

hard campaigning.

Not wishing to force another head long battle in open terrain he resolved upon a daring

flank attack across a couple of rivers and through marshland. Leaving small forces to hold

Verona and the line of the Adige river near it he marched to Ronco and attacked with the

goal of taking the town of Arcola on the far side of the Alpone river, and an area marshland to

the east and north of the bigger Adige.

Most importantly Arcola was clearly in the rear of any army before Verona and once Bonaparte

had established himself there he'd be a clear threat to the rear and communications of

Alvintzy's army.

At dawn on the 15th of November Massena's and Augureau's divisions crossed the Adige at Ronco.

Messena deployed north west to Belifiore di Porcile to defend Augereau's flank while he attacked

towards Arcola. Despite Bonaparte's direct participation in the fighting Augureau's attack failed.

A smaller French force (Guieu's brigade) did cross in boats and take the town from the south later but

Augereau and Massena had both already withdrawn. Guieu elected to do the same.

So on the ground the first day looked like a tactical failure despite heroic efforts and high losses.

Strategically however it had succeeded in convincing Alventzy to call off a planned attack on Verona and to

withdraw forces to cover the French threat to his flank.

The 16th saw Massena and Augereau repeating their efforts of the 15th. In the process they met

Austrian forces advancing on the French bridgehead at Ronco. The Austrians were severely mauled.

Once again, however, Augereau failed to take Arcola and Bonaparte withdrew his forces to the

bridgehead at Ronco.

During the night of the 16th/17th French engineers built a bridge over the Alpone south of Arcola and just

north of where the Alpone joins the Adige.

On the 17the Massena as well as guarding the bridgehead made a demonstration along the route Augereau had taken the

two previous days. While Messena dealt severe blows to the Austrian forces sent against him, Augereau's division

was crossing the Alpone over the bridge built the night before.

Their flank turned by Augereau the Austrians withdrew after some hard fighting.

The French admitted losses of about 4,600 men.

The Austrians losses exceeded 6,000 men.

The battles around Arcola left the troops of both sides physically exhausted. Morally and strategically

the victory went to Bonaparte and the French. They had stymied the third Austrian attempt to relieve

Mantua.

|

14 January 1797

|

French Army of Italy under General Bonaparte

using divisions of Joubert, Rey, and Massena totalling

approximately 21,000 men.

|

Austrian army under General (FZM) Alvintzy with

about 28,000 men.

|

|

Rivoli was the culmination of the Austrian's fourth attempt, the second under Alvintzy, to relieve

Mantua.

Alvintzy this time attacked straight down the line of the Adige from Trent towards Verona.

He did so in several columns which although perhaps close on the map or as the crows flies were

not necessarily in easy communication due to the north-south trend of the mountainous terrain.

In particular the troops marching in the mountain valleys above and to the west of the river

bottom where the road that could take wagons and guns ran were effectively out of supporting

range. The place where the river road and the mountain roads connected again was Rivoli.

And that's where the defending troops of the 10,000 man strong division under Joubert made their

stand on the 13th of January 1797.

This time it had been Bonaparte who'd been caught a bit off guard, but he reacted quickly.

He ordered a variety of reinforcements for Joubert including most importantly, Massena's division

of almost 10,000 men.

Bonaparte himself was present on the battlefield by 0200 on the 14th. He immediately ordered a

counterattack to take key tactical features.

Throughout the morning of the 14th Massena's troop's arrived and were thrown in to save the

desperate French defense. By the afternoon the Austrians were defeated and the French

ready to begin their pursuit.

An attempt by Alvintzy to counter-attack on the 15th was a dismal failure.

The French casualties were some 5,000 men.

The Austrians lost around 14,000 men; many of them prisoners.

The outcome of Rivoli was not just the defeat of the third and last effort to relieve

Mantua, but the destruction of the Austrian Field Army in Italy and the complete demoralization

of its remenants. Mantua surrendered several weeks later. In the spring Bonaparte marched on Vienna.

|

Battle of the Pyramids ,

Battle of the Nile ,

Mount Tabor ,

First Aboukir ,

Heliopolis ,

Second Aboukir,

21 July 1798

|

The French Army of the Orient with around 28,000 men,

General Bonaparte commanding.

|

A Mameluke commanded Eygptian force with about 24,000 men and 30 guns.

Most of the force was poor grade infantry,

its core was its Mameluke cavalry consisting of at most 6,000 men.

Murad Bey commanded that part of the Eygptian force actually engaged.

|

|

Bonaparte having made it most of the way to Cairo the Mamelukes resolved to meet him.

They did so on on the west side of the Nile facing north, on their right near the Nile was most of their infantry

and their guns entrenched around and in the the village of Embabeh. On their left was their

heretofore unbeaten Mameluke cavalry.

Bonaparte being vastly inferior in cavalry formed his forces into five large divisional squares.

He integrated his artillery with these squares and kept any vulnerable "rear" elements protected within them

From the left near the Nile to the right on the desert flank these divisional formations were those of

Bon, Vial, Dugua, Reynier and Desaix.

It was mid-afternoon before the Mameluke's cavalry opened the battle with a wild charge at

Desaix's and Reynier's squares. They were unable to make headway against the superior discipline and

firepower of the French and but took heavy losses in ferocious attempts.

In the meantime the divisions of Bon and Vial took the village of Embabeh and slaughtered the

troops there. The day ended with the Eygptians defeated and in flight.

The French losses were about 300 men.

The Eygptians lost about 5,000 men in casualties, many of them Mamelukes.

The previously demoralized and almost mutinous French troops enjoyed much rich looting.

Cairo the key to Eygpt fell to Bonaparte's forces.

|

1 August 1798

|

The British Mediterrean Fleet under Admiral Nelson with

14 ships of the line and 7 frigates.

|

The French Fleet under Admiral Bruey with

13 ships of the line and 4 frigates.

.

|

|

Nelson had been seeking the French Fleet for some time. He was mortified at having

missed it earlier and having allowed Bonaparte to land in Eygpt.

Coming into sight of it anchored at around four in the afternoon, with less than three

hours of daylight left, the British fleet nevertheless attacked.

By direct order or prearrangement is unclear. Whatever the facts of the occassion

Nelson had long made it explicitly clear that he would immediately attack the French

Fleet when he found it, that he would fight at night if need be (means of identification

and signals were prearranged), and that if he found the French at anchor he would attempt

to pass his leading ships between French ships and the shore.

The British believed "[w]here there was room for a French ship to swing [at anchor] there

was room for an English ship to pass". And having passed they would be able to

engage the closest half of the French ships from both sides; two on one, the leading half of the

British fleet from the shore side, the rear half from the sea side.

And that's what happened. Not without mishap, or notable incidents. One English ship went

aground, and the French flagship exploded in a manner that was spectacular beyond expectation, but

basically that's what happened.

And it worked. The French fleet was all but annihilated.

The British lost 218 men killed, 678 wounded.

The French lost 1,700 men dead and 1,500 wounded, 11 ships of the line,

and 2 frigates.

A couple of thousand French prisoners were released and put ashore.

The fate of Bonaparte's Army of the Orient was determined by this naval battle. The Mediterrean had

become a British lake and his army was cut-off. The French in Eygpt would receive no further supplies

or men, and when they tried to move their heavy seige guns to Syria by sea, those vital strategic assets

were captured and used against them.

|

16 April 1799

|

The French Army of the Orient with around 4,000 men in the end,

an initial 2,000 under General Kleber and another 2,000 in the relief

column commanded by General Bonaparte.

|

The Ottoman Army of Damascus with about 35,000 men,

Achmed Bey commanding.

|

|

Bonaparte was beseiging Acre, the Ottomans had raised an army at Damascus which was

marching to relieve it. Bonaparte sent Kleber with a very small division to intercept

and defeat this threat.

Kleber intended a night march to surprise the Ottoman force early in the morning while it

was still dark.

He mistimed his movements and ended up encountering the Ottomans after sunrise.

Kleber's heavily outnumbered force spent the day in two small squares sucessfully

beating off every attack but unable to move or break ranks even to reach the

water they could plainly see close by. It was a temporary stalemate that didn't

bode well for the French.

Bonaparte, in the meantime, either hearing the guns or having expected the turn of

events, was marching to Kleber's relief.

He arrived in time around four in the afternoon. A few cannon shots through the

attacking Ottomans into disarray and Kleber and Bonaparte moved together to

inflict heavy losses on their fleeing foes.

The French losses were about 300 men.

The Ottomans lost about 5,000 men.

One of the two main armies the Ottamans had been organizing to retake Eygpt was defeated.

The French seige of Acre continued. In the event, it failed and Bonaparte was forced

to retreat to Eygpt with a much diminished and demoralized army. Without the victory

at Mount Tabor he might not have been even so lucky.

|

25 July 1799

|

The French Army of the Orient with around 7,700 men and 17 guns,

General Bonaparte commanding.

|

The Ottoman Army of Rhodes with about 18,000 men,

Mustafa Pasha commanding.

|

|

With British help the Ottomans landed the Army of Rhodes at Aboukir overwhelming the

small French garrison that'd been left there. They then dug in to await both their own

reinforcements and the likely French counterattack. They did so in three lines behind

which they held the Fort of Aboukir itself.

Bonaparte rapidly concentrated his forces and marched to the attack.

His infantry with able assistance from his artillery took each line of fortifications in

succession. In numbers they were not far inferior to each successive set of Ottoman

defenders and their organization and discipline were far superiour and their guns much

more ably handled. The newly formed French cavalry turned the Ottoman defeat into a

rout that had no where to go.

The French casualties were about 900 men around 200 killed outright.

The Ottomans lost about 13,000 killed outright, 3,000 prisoners,

and 2,000 missing.

The Ottoman Turk attempts to recover Eygpt were decisively defeated. The French had

been whittled down but faced no immediate threat to their control of Eygpt. It was

not unreasonable to expect that in the event of a general peace they might be able

to retain possession of the country.

|

20 March 1800

|

The French Army of the Orient with around 10,000 men,

General Kleber commanding.

|

An Ottoman Army from Syria with about 40,000 men,

Ibrahim Bey commanding.

|

|

General Kleber, who'd been left to hold Eygpt by Bonaparte, had been attempting to

negotiate the safe evacuation of his Army back to France.

He was facing a very large Ottoman army of at least 40,000 camped just outside of

Cairo at the ancient site of Heliopolis.

For whatever reason, it's still a subject of controversy, the negotiations broke

down and Kleber resolved on a surprise attack at dawn with the aim of removing the

Ottoman threat.

The attack was a success. Only a fraction of the Ottoman army put up a real

resistance and once their camp was taken the Ottoman force disintegrated.

The French casualties were about 300 men .

The Ottomans lost about 6,000 men as a very uncertain estimate, and,

more precisely, 19 guns.

The main and most immediate threat to the French position in Eygpt was removed.

Cairo had to be retaken from a small force that had seized it while the main battle

at Heliopolis was being fought. Other revolts and unrest among the local population

also needed to be supressed, but the Ottomans alone no longer posed a serious threat

to the French control of Eygpt. The British would have to send their own forces

if they wished to contest it.

|

20-21 March 1801, Also known as Battle of Alexandria.

|

The French Army of the Orient with around 10,000 men,

General Menou commanding.

|

A British Army with about 12,000 effectives,

General Abercromby commanding.

|

|

The British had begun landing at Aboukir Bay on the 8th March, by the 18th they'd

taken Aboukir Castle.

Their main army was at the time in positions just short of 5km from Alexandria.

Menou, who'd taken command after General Kleber's assasination, reached Alexandria

with the main French field force on the 19th. He attacked the British during the

night of the 20th.

General Moore who was in command until General Abercromby's arrival was able to

discern the main French attacks and commit his reserves appropriately. The British,

although hard pressed, managed to hold and inflict heavy casualities on the French.

Their own losses were not light and included General Abercromby himself.

The French suffered about 3,000 casualties.

The British casualties were about 1,400 men killed or wounded.

The British had proven they could meet the French on equal terms

Menou retreated into Alexandria. The British put Alexandria under seige splitting the French forces in Egypt. They marched on Cairo where the largest French presence, some 12,000 men, under General Belliard was.

Menou's Army was intact and still held much of Eygpt but

its position was no longer tenable.

|

Montebello ,

Marengo

9 June 1800

|

The Advance Guard of the French Army of the Reserve with around 8,000 men,

General Lannes commanding.

Later reinforced by General Victor's

Corps of 5,000 men.

|

An Austrian column with about 18,000 men, and 35 guns,

General Ott commanding.

|

|

The French and Austrian's were both manouvering in confusion and ignorance of each others

positions.

Lannes had crossed the Po and was moving west between its southern bank and the Appennines

towards Voghera when he met Ott's force, which had just taken up positions at Casteggio,

head on.

Initially he was repulsed. But after Victor arrived with reinforcements, he broke Ott's

forces and pursued them through Montebello.

The French casualties were about 500 men .

The Austrians lost about 4,000 .

The French had finally gained some idea of where the Austrian's were.

And if the situation wasn't as rosy as Napoleon had thought, the battle at Montebello did

give the Austrians some pause leading them to undertake a cautious plan of concentrating at

Alessandria rather than attempting something more aggressive.

|

14 June 1800

|

The French Army of the Reserve with around 15,000 men at first

reinforced to 23,000 men. The French likely had 42 guns.

General Berthier

was in nominal command, the actual command was held by

Napoleon who was

technically still just "First Consul Bonaparte".

|

The Austrian Army of Italy with about 35,000 men with 100 guns,

General Melas commanding.

|

|

Napoleon thought he was pursuing an Austrian Army that was trying to evade him and regain

secure lines of supply, either by passing north of Po and marching east or by marching south

to Genoa where the Royal Navy could ensure its supply by sea.

By the 13th he was facing, if not completely in contact, with the main Austrian army at

Alessandria, between them lay the plain between the river Scrivia and the Bromida river, and

most importantly the Bromida river itself.

At this point he chose to detach two divisions one north and one south to keep the Austrians

from getting away. In the process he reduced his strength to almost half of that of the

main Austrian army and certainly no more than two thirds of it.

As a consequence when the Austrians attacked on the morning of the 14th the French

situation rapidly became serious.

Despite the restriction posed by the bridges over the Bromida and general Austrian

ponderousness by eleven in the morning the French

were being forced back along their entire line and were in danger of breaking.

At this point Napoleon finally realizing his danger sent messages off to recall the divisions

he'd sent north and south earlier in the day. He also ordered his reserves, the Guard and Monnier's division forward.

Conveniently for the French the Austrians chose to take an hour at midday to pause and re-group.

By 1300 their attack had resumed, and by 1400 Victor's position in Marengo was desperate, and an Austrian

Force under General Ott was threatening to turn the French right and cut the line of retreat for the French

center. The bulk of the French army faced annilhilation.

Rather than reinforcing his crumbling center Napoleon deployed his reserves to face Ott on the right.

This prevented an envelopment but between 1400 and 1500 the French were again being forced back all along their line.

Their withdrawal remained orderly, partly because the Austrian cavalry had been completely committed, but they'd

clearly been defeated. At about 1500 the Austrian Commander in Chief Melas, old and battered from a hard day's fight,

chose to turn the pursuit over to his subordinate Zach and leave the field.

At about this point Desaix with Boudet's division which had been sent south close behind him arrived

on the field of battle. He is famously suppossed to have told Napoleon that although one battle

had been lost there was still time to win another.

That the Austrians under Zach took until 1630 to organize their pursuit gave the retreating French

troops time to rally, and Desaix time to deploy Boudet's fresh division south of the road along which

the Austrian pursuit would come.

The Austrian pursuit column in the center essentially walked into a gigantic unexpected ambush.

It broke, and routed, fled. The flanking Austrian forces were left hanging in the air.

The French defeat had become a victory, but a very expensive one. The price included the life

of Desaix who'd been killed leading the counter-attack.

The French casualties were about 7,000 men.

The Austrians had roughly 6,000 men killed, lost 40 guns and had 8,000

men taken prisoner.

As First Consul, Napoleon's political position was still fragile. He had needed victory and

and he took pains to re-write the record to make Marengo appear more of one than it was.

He had planned on annihilating Melas army and was forced to allow it retire more or less

intact; his own army being considerably battered. He was forced to wait most of the year

for Moreau in Germany to achieve a sufficiently great victory at Hohenlinden that the Austrians

were compelled to make peace.

A less than ideal outcome from the First Consul's point of view, first the war weary French were

forced to wait for peace and then it came as the result of the success of a rival general.

Still an outright defeat at Marengo might have ended his career.

|

Second Stockach ,

Hochstadt ,

Hohenlinden

3 May 1800

|

The French Army of the Rhine with around 28,000 men belonging to the

French right wing under General LeCourbe actually engaged,

General Moreau in overall command.

|

The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine with about 9,000 men of

Prince Joseph of Lorraine detachment actually engaged,

General (FZM) Kray commanding overall.

|

|

Stockach was a major depot on the main Austrian line of communications to its armies on the Upper

Rhine throughout the wars of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods. Lake Constance lies just a few

kilometers to the south-east. The upper Danube is 20 to 25 kilometers north of it, in a rougher more

forested area. Stockach was also frequently the location of the Austrian Army's HQ in this period.

In the spring of 1800 the French used their control of Switzerland to flank the main Austrian force

by crossing the Rhine at Schaffhuasen in strength. The fortress at Hohentweil meant to secure the Austrian flank

in this area quickly surrendered.

The result being that on the 3rd of May while the French and Austrian main forces under Moreau and Kray

respectively slugged it out at Engen about 20 km west of Stockach, an Austrian force under the

Prince of Lorraine was overwhelmed by a vastly superior force consisting of the French Right wing Corps commanded by

General Lecourbe.

The French losses were about 2,000 men.

The Austrians lost about 2,000 men.

Although the main action at Engen was at least a draw on hearing of the loss of Stockach Kray ordered an Austrian

retreat that ended in his force being forced all the way back to the fortifications at Ulm. The loss of Stockach

had unhinged the entire Austrian postion. It also directly resulted in considerable losses of stores as well as the rout and

considerable loss to the Austrian forces engaged there.

|

19 June 1800

|

The French Army of the Rhine with around 25,000 men of

General Lecourbe's right wing Corps engaged,

General Moreau commanding overall.

|

The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine with about 70,000 men,

General (FZM) Kray commanding overall.

Main part of engagement fought by what was originally the Austrian right wing commanded by

General (FZM) Sztarray with about 16,000 men.

|

|

General Kray's main force was in Ulm but he was again flanked by Moreau's right wing under General Lecourbe

who managed a surprise river crossing of the Danube some 60km down river near Hochstadt (close to the site

of Marlbourough's famous victory at Blenhiem).

Despite hard fighting by General Sztarray's forces the French managed to gain control of both sides of the river

severing Austrian supply lines once again.

The French losses are uncertain but not likely more than a few hundred.

The Austrians lost about 1,000 men killed and wounded and another "several thousand" taken prisoner.

Kray was forced to abandon Ulm and ulitimately most of Bavaria.

|

3 December 1800

|

The French Army of the Rhine with around 100,000 men engaged,

General Moreau commanding.

|

The Austrian Army of the Upper Rhine with about 130,000 men,

Archduke John commanding.

|

|

Hohenlinden is about 30km east of Munich near the Inn Valley

The Archduke John thought the French were in retreat and was attacking towards Munich in multiple columns.

It was snowy and the going was bad, the columns made poor time especially the flanking ones, and were out of

touch with each other. In particular his left wing column had become lost.