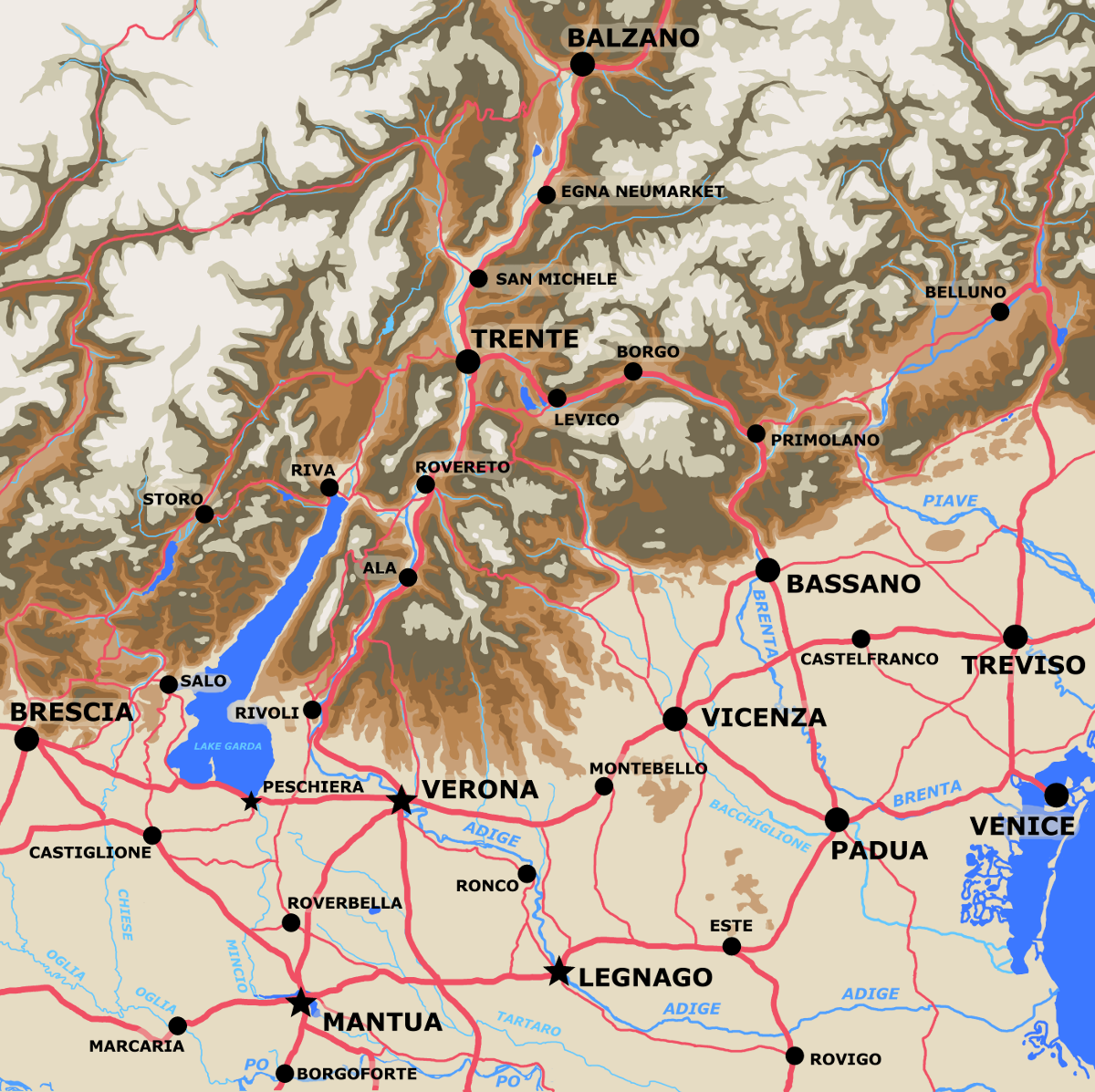

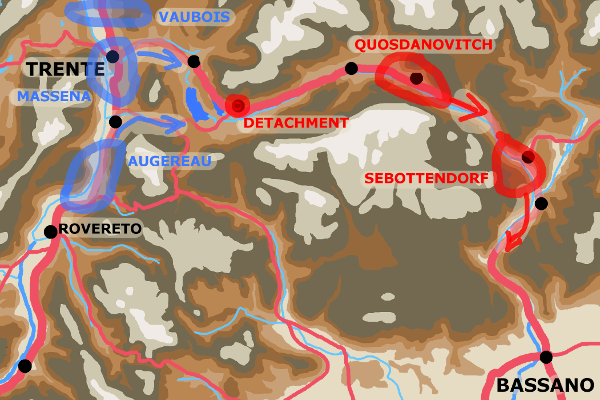

Map of Adige Valley from Borghetto to Bolzano

September 2nd

September 3rd

September 4th

September 5th

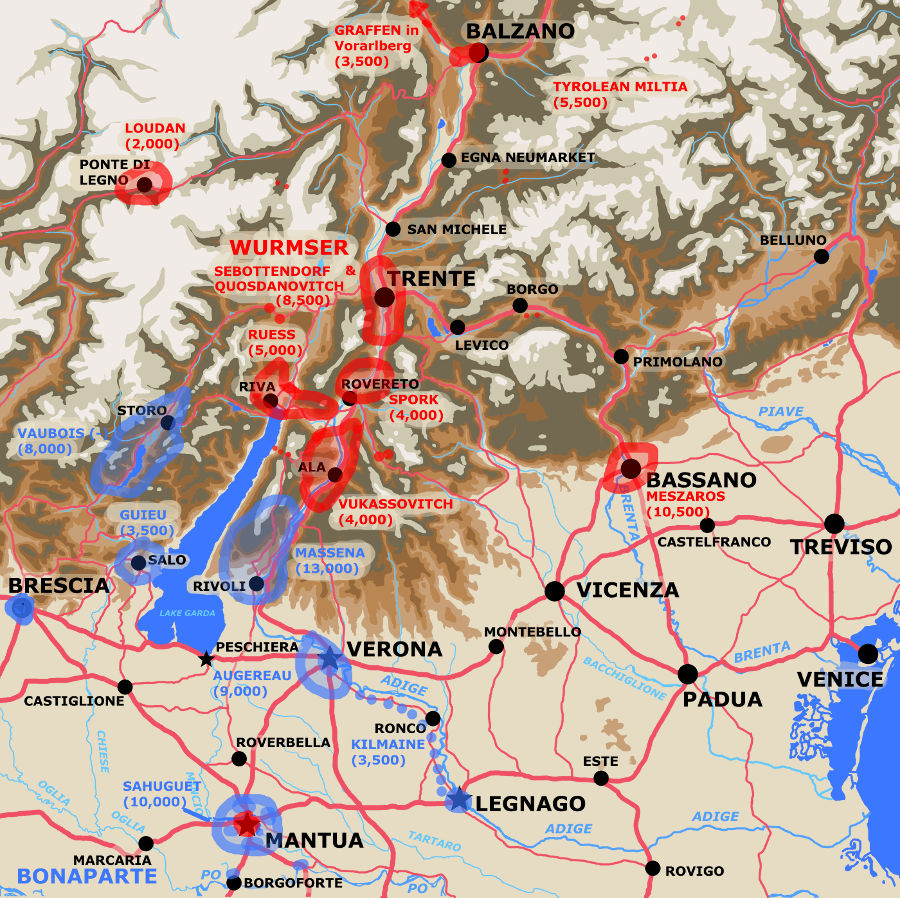

Wurmser Advances to relieve Bonaparte's Army of Italy's blockade of Mantua.

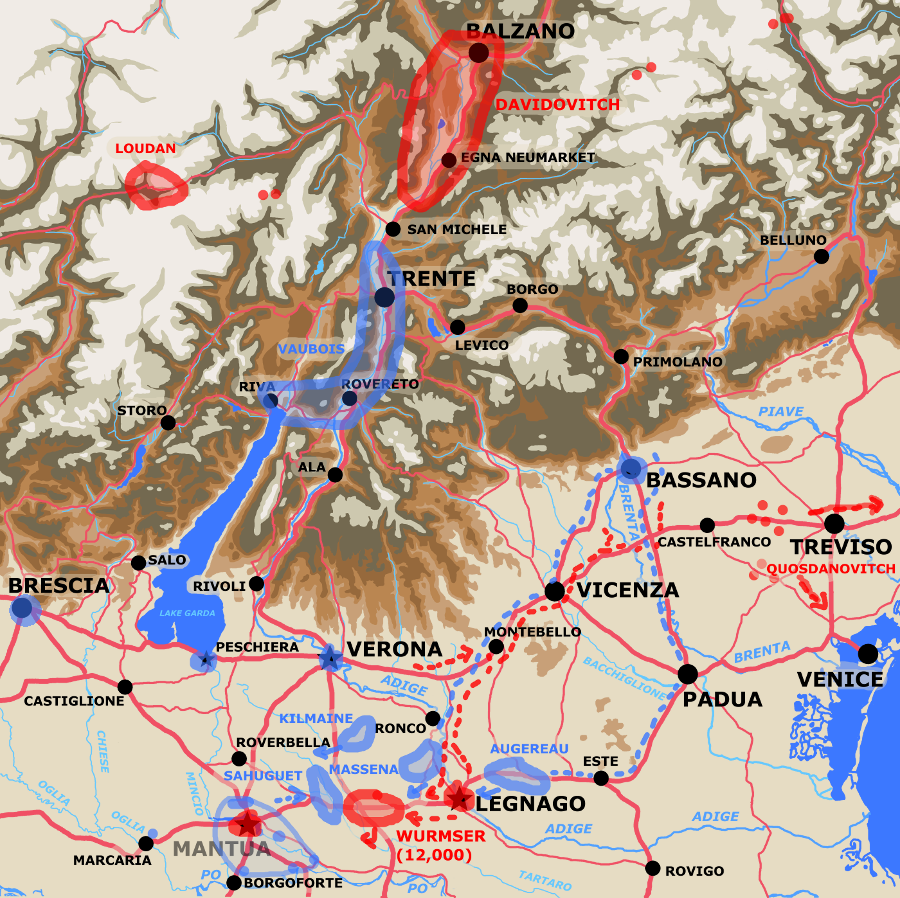

Map of Theatre of Operations August 28th to September 15th 1796.

Map of Theatre of Operations August 28th showing forces available.

Neither the Austrian nor the French armies were ready for another campaign less than month after the grueling Castiglione campaign.

Despite this the governments of both France and Austria demanded action.

We know more about the French problems. Their supply chain, never entirely adequate, was thrown into complete disarray by the deep Austrian penetrations of the Castiglione Campaign and the Italian revolts that accompanied them. Many French officials simply fled abandoning their responsibilities. The French troops were exhausted from forced march after forced march interspered with days of hard fighting. They were often left without food, drink, proper clothing or footware. At times even weapons were lacking. The ranks of the officers needed to advocate for them and to inspire them to action despite material deficencies had been thinned in combat.

Originally Bonaparte had wanted to march in late August. There is a letter from him dated August 18th (#906) in which he states he needs supplies to be able to march in 4 or 5 days. As he didn't do so one must surmise the needed supplies were not forthcoming.

Certainly Massena bitterly complained his troops were naked and starving and physically not able to conduct a viable offensive. Augereau left a whole newly arrived regiment (the 29th) behind when he marched because of its being so poorly equiped. Sauret and Vaubois both complained that the supplies supposedly sent them never arrived in their entirety at their outposts in the mountains west of Lake Garda.

Still Bonaparte had told Moreau and the Directory he would march to into the Alps in order to link up with Moreau's army in Germany and he insisted the attack go forward. He issued orders to move on September the 2nd.

There'd been some changes in the command ranks of the French Army mainly due to illness. Sauret had been replaced by Vaubois. Serurier had been replaced by Sahuguet. Kilmaine was given command of a mixed group of cavalry and infantry and the task of screening the army's rear. He had garrisons in Verona and Legnago and a thin line of troops screening the banks of the Adige in between. He was to defend against attacks from the east, holding the key crossings, especially that at Verona, as long as possible and calling on help from Sahuguet as needed.

Sahuguet had the task of blockading Mantua. Massena, Augureau and Vaubois formed the army's striking force.

French Order of Battle beginning of September 1796

The whole French force in the immediate area of operations was 46,500 men.

Regards the Austrians we must remember first of at all they were in the mountains so local supplies were limited and their supply lines long and difficult. We know they had lost a considerable amount of equipment just weeks before. The French picked up many cannon that had been left behind and muskets that had been thrown away by the retreating Austrian troops especially those of Quosdanovich.

If the accounts of the English colonel Thomas Graham are to believed morale was not good. He has the troops willing but lacking faith in their generals. The saying " we must make peace because we cannot make war " was making the rounds.

Wurmser was in overall command. He intended to personally command the half of the Army that was going to strike at the French via the Brenta valley, Bassano, and Vicenza. Davidovitch was left in charge of the half of the army charged with defending the Tyrol. Significant portions of Davidovitch's force were deployed against threats other than Bonaparte's Army of Italy. For that he had only the brigades of Spork, Reuss and Vukassovitch.

Overall the Austrians had a combat force of about 52,500 men available, but discounting the Tyrolean militia, and Graffen's and Laudon's commands only about 43,000 to oppose Bonaparte.

In summary the available combat forces for each side were equal at about 43,000 men. Considering the garrison at Mantua and the blockading force there to cancel out that would be about 33,000 men available for each side's field force. Given that Bonaparte was more or less concentrated while the had Austrians divided their force into two parts of of 13,500 and 19,500, and that Bonaparte was able to draw down his blocking force by several thousand for field operations once the battle reached the area of Mantua, Bonaparte had an effective advantage of a few thousand men. By the dint of faster French marching and decision making this translated to much better numeric advantages at both Rovereto and Bassano.

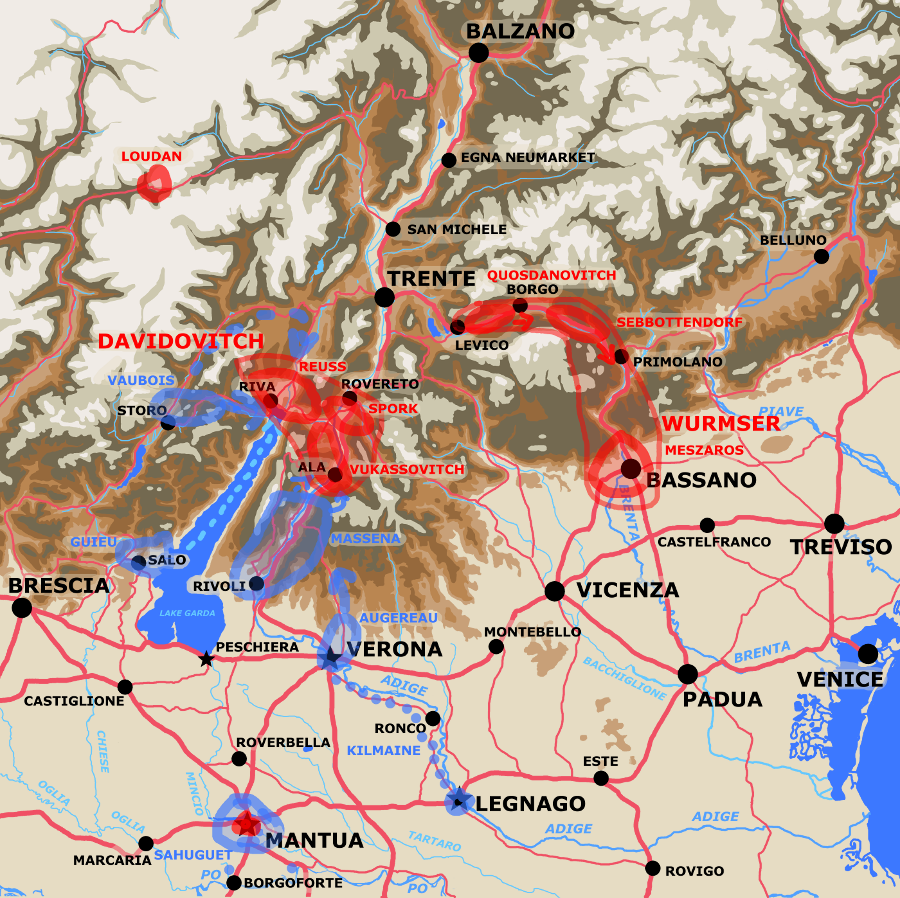

Map Showing situation September 2nd 1796

In the event the Austrians jumped off a day sooner than the French on September 1st. Sebottendorf moving off in the morning to march down the Brenta river valley to join Meszaros. Sebottendorf reached Pegrine about half way to Levico that day and Levico on the 2nd. Quosdanovitch followed reaching Pegrine on the 2nd. (See maps of the Val de Saguna starting September 5th below.)

The second of September saw the beginning of the French movements. Massena marched north up the Adige valley using the good road on the eastern side of the river. Augereau took a route from Verona through the mountains to the east via Lugo. To the west on the other side of Lake Garda, Vaubois moved out of Stora to march on Riva with two brigades. A third brigade of Vaubois's under Guieu that had been at Salo boarded boats with the intent of landing at Torbole the next day.

On September the third Massena took Ala from troops under Vukassovitch and Vaubois drove Reuss out of Nago and Torbole. Guieu successfully landed in Torbole in the evening. Wurmser ordered counter attacks for dawn on the 4th. He allowed Sebottendorf and Quosdanovitch to continue on their ways, and ordered Meszaro to advance on Verona on the 4th. He was moving these forces away from Davidovich in the apparent belief that if he threatened Bonaparte's line of communications through Verona that the French would be forced to withdraw down the Adige the way they came. Possibly he thought Davidovich could hold and that he stood a chance of trapping and destroying the French army in the valley of the Adige.

On the evening of the 3rd the leader of Massena's advance guard General Pijon took Serraville and Vukassovitch retreated to Marco.

The 4th of September saw the battle of Rovereto. The French jumped off during the early hours. They intended to concentrate at Roverto around 8 or 9 in the morning. Around daybreak Davidovich reached Marco with Spork's brigade which took up a position in support of Vukassovich. Faced with the full weight of Massena's division Vukassovich was forced out of Marco while at the same time Vaubois took Mori from Ruess. Mori is near to, but on the other side of the Adige from Marco. By midday Vukassovich was fighting in Rovereto which he'd lost by one in the afternoon. During the afternoon the survivors of Vukassovich's brigade and Spork's brigade were surprised by the French north of Rovereto at Calliano. Apparently they'd depended on the natural strength of the approaches and a small detachment of defenders for safety. In the event Massena's men attacking at four in the afternoon routed them.

Wurmser in Trent learned of the disaster at Rovereto at 5:30pm on the 4th. He ordered Reuss to hold Trent. Sebottendorf had reached Ospedaletto and Quosdanovich Borgo. They'd gone too far to be able to counter march to Trent before the French arrived. Wurmser himself left for Bassano and his part of the army continued their march.

Davidovich abandoned Trent on the night of the 4th and the 5th. He only had 5,000 men left, the brigades of Spork and Vukassovich having been mostly destroyed. He moved back with the remnants of those brigades and Ruess to Lavis where he formed an outpost line.

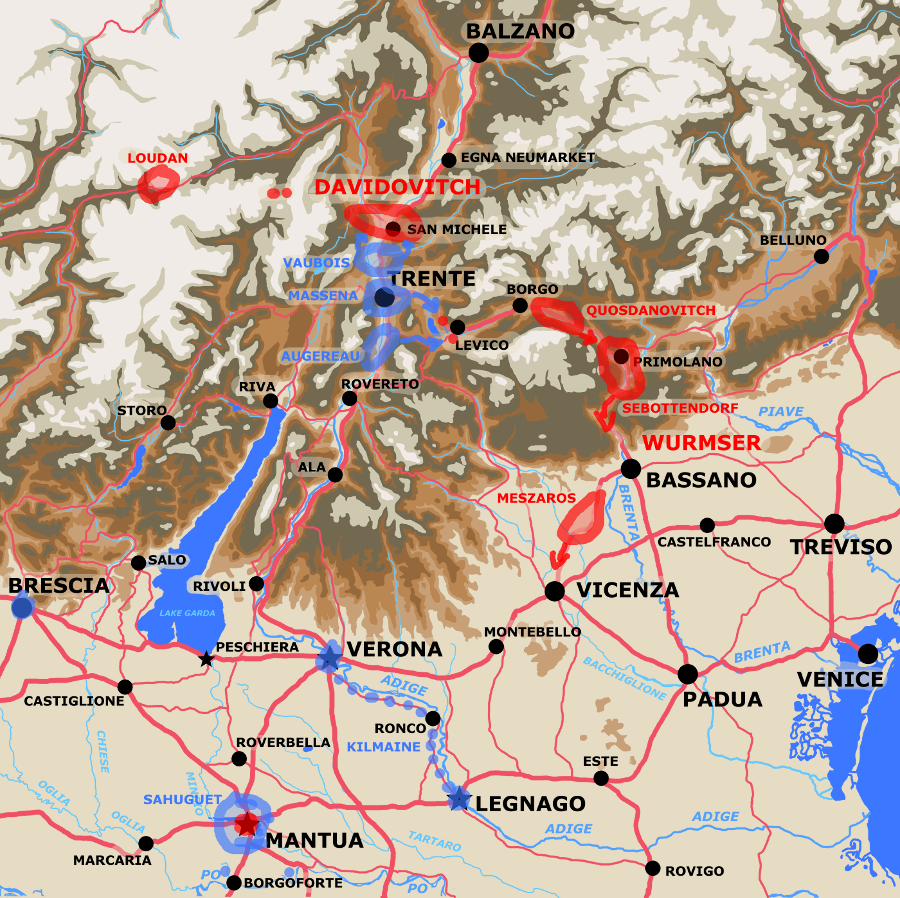

Massena reached Trent at 8:00am on the 5th. Vaubois had crossed the Adige and was following close behind him. It was at this time that Bonaparte first realized that Wurmser had taken a substantial portion of his army and marched down the Brenta river valley to Bassano.

If Bonaparte had done as Wurmser expected he would have counter marched down the Adige valley to the vicenity of Verona. If he'd done as he'd planned and the Directory had ordered he'd have continued north to link with Moreau's army in Germany. He did neither. He decided to follow Wurmser's army in its march down the Brenta river to Bassano.

Maps showing operations in the valley of the Adige around Rovereto from September 2nd to 5th.

Map of Adige Valley from Borghetto to Bolzano

|

September 2nd

|

September 3rd

|

September 4th

|

September 5th

|

See the battles page entry for Rovereto for more details.

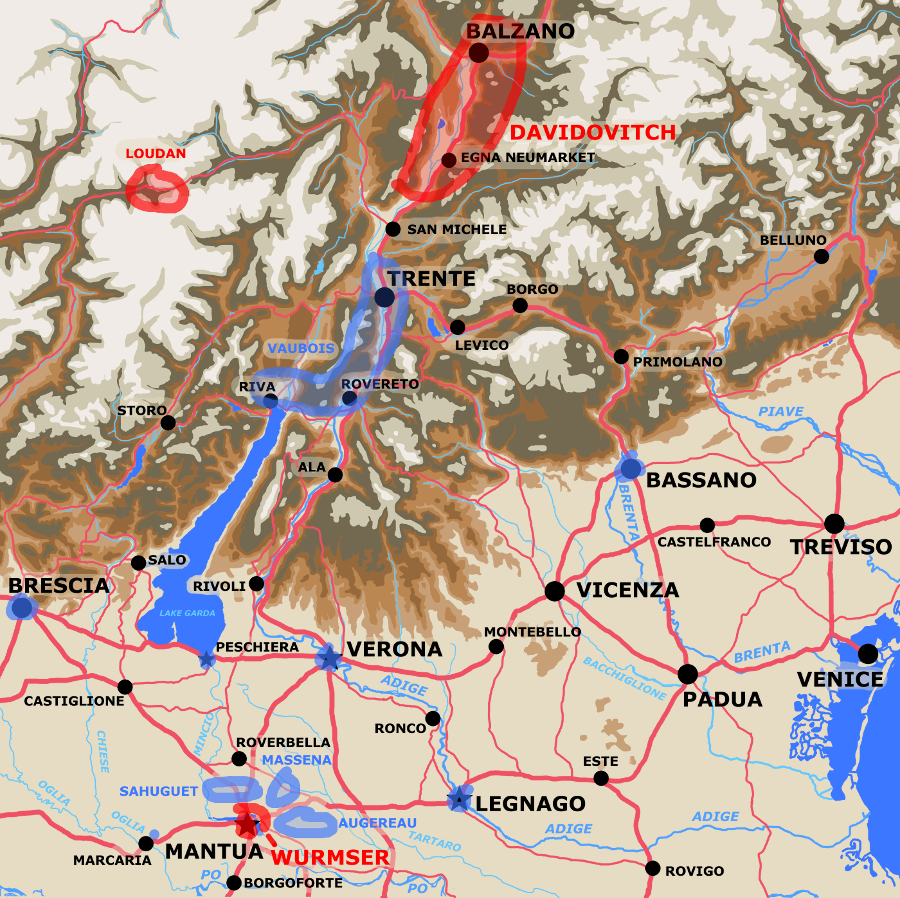

Map Showing situation September 5th 1796

In after the fact assessments Wurmser's decision to continue to move down the Brenta valley with Sebottendorf's and Quosdanovich troops, and to push Meszaros forward in an attack on Verona, appears as misguided as Bonaparte's decision to follow him appears brilliant.

The truth, arrived at by looking at the situation as it appeared at the time to the opposing generals and not in the light of we now know, is that Bonaparte was brilliant, but Wurmser was also very good but operating based on outworn understandings.

Without a secure line of communications or supplies trapped in a narrow mountain valley between two well supplied enemy armies both easily able to defend themselves because of almost equal numbers in very defensible terrain, the French Army of Italy should have faced certain destruction. All conventional military experience and theory said so. Moreover remember Wurmser had experience defeating French Revolutionary armies in Germany. They were fearsome and unpredictable in the attack, often achieving successes beyond those possible to conventional eighteenth century armies. Once checked their morale tended to falter. Momentum having been lost, without fresh territory to forage in, and without the organization to defend themselves in static positions, French Revolutionary armies tended to fall apart and to scramble to the rear almost as quickly as they'd scrambled forward. Wurmser had every right to expect this would be true of the Army of Italy but Bonaparte never allowed it to happen.

The French could march twice as far as old regieme armies had each day, day after day. Their men if anything were in poorer shape than those of their enemies, but they were motivated, and driven on by officers who marched with them and shared their privations. Bonaparte made good use of these facts.

Bonaparte also proved much more adept at overcoming defensive positions in the mountains than the Austrians expected. The French overcame a whole series of defensible positions around Roverto and then they overwhelmed a whole series of detachments that Wurmser had Quosdanovitch leave behind in blocking positions in the Brenta valley to delay them.

Quosdanovich's strength was whittled away in penny packets with out any significant delay on the pursuing French being imposed.

The reasons the Austrian's rational expectations were not met, are in some degree speculative.

They appear to have been three fold:

These facts meant the French under Bonaparte could, and did routinely, attack an Austrian position to the front holding the Austrian troops in place while light troops worked around through difficult, often theoretically impassable, terrain on their flanks threatening those flanks, and the rear of the Austrians also. The Austrians facing attack on all sides and with the prospect of having their line of retreat cut off, would, sometimes after an initial hard fight, retreat to save themselves. Positions that would have significantly delayed a conventional army attacking head on in the little good terrain available, and leary of disproportionate losses, instead fell quickly.

Actions of this sort played out on the three successive days of the 5th, 6th, and 7th. Austrian detachments were winkled out of Levico, Primolano, and the fort of Cevolo. By the night of the 7th Bonaparte was in Cismon with his advance guard. He'd caught up with with Sebottondorf and Quosdanovich, decimating Quosdanovich in the process. The next morning he'd march on Bassano.

Map of the Val di Saguna, the Brenta valley from Trent to Bassano

September 5th

|

September 6th

|

September 7th

|

September 8th

|

Map Showing situation September 8th 1796

Meszaro with 10,000 plus men, about half of Wurmser's original force, reached and attacked Verona on September the 7th.

Kilmaine opposed him with only 3,500 men. In addition to Verona, Kilmaine was charged with patrolling the line of the Adige down to Legnago, and holding Legnago too.

Verona, however, was both a major city and heavily fortified. Wurmser's trains, his pontoon bridges and much of his artillery, were still back at Bassano. Meszaro's force was not ideally tailored for an attack on a fortified city, even one with a garrison much smaller than his attacking force.

The West Point Atlas indicates that his initial attack having failed Meszaro's requested reinforcements and pontoons from Wurmser. Instead he got orders to move back towards Bassano. The exact timing of this exchange is unclear. It seems probable that Wurmser made this decision to order Meszaro's forces back late on the 7th. It is recorded that he had his trains, and Sebottendorf's and Quosdanovich's brigades remain on guard at Bassano that night. I believe it's a reasonable surmise that his intent was concentrate his entire force near Bassano and deal with Bonaparte's army as it exited the mountains.

In the event the French moved too quickly. They set off from Cismon at 2:00 am on the 8th. By 7:00 am they had engaged the vastly outnumbered Austians at Solagna and Campo Lungo north of Bassano just before the valley of the Brenta widens out. Despite restricted terrain hampering the full use of their superior numbers the French rapidly overran the Austrian brigades. That General Bajalich was captured in the rout is some indication of just how badly the Austrians were beaten.

Messena and Augereau fighting Sebottendorf and Quosdanovitch respectively, on the west and east sides of Adige, drove on into Bassano where they caught both Wurmser's reserves and his trains. The Austrian troops were caught jammed into the narrow streets of the town.

Many prisoners (3,000 to 5,000), 35 guns, two pontoon bridges, and hundreds of wagons were captured.

The fugitive remains of the Austrian army split into two. One set of troops under Quosdanovitch retreated south and east via CastelFranco towards Treviso, and eventually Trieste. The others under Sebottendorf and Wurmser retreated west and south. Many including Wurmser to Cittadella and Fontanavia near it on the Brenta.

As Adlow writes "On the afternoon of the 8th Wurmser crossed the Brenta at Fontaniva and moved on Vicenza, where he rejoined Sebottendorf. From here he moved on Legnago by Montebellow, where Meszros rejoined him. He still had 12,000 infantry and 3,000 horse, and decided to move on Mantua. Detachments from Meszaros had in the meantime seized Legnago. This secured for Wurmser the means of crossing the Adige."

See the battles page entry for Bassano for more details.

Bonaparte thought it was most likely Wurmser would retreat on Trieste and he sent Augereau south through Cittedella to Padua to prevent this. Augereau reached Padua on the 9th. Messena was dispatched west reaching Vicenza on the 9th. As Martin Boycott-Brown writes "Wurmser arrived in Montebello before dawn on the 9th and, being concerned to secure the crossing at Legnago, the shortest route to Mantua now that he had no bridging train, a detachment was sent to occupy it."

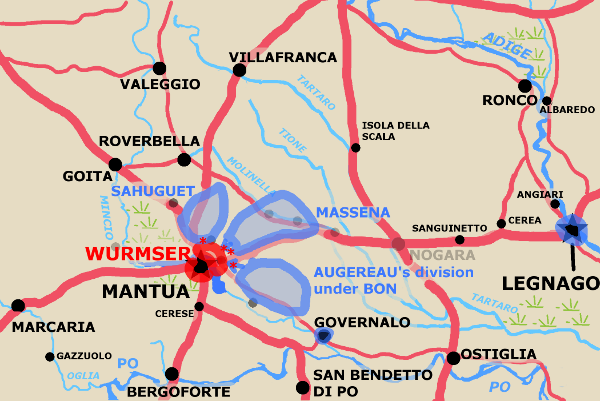

Map of the area between Bassano and Mantua, area of operations from September 8th to 11th.

September 8th

|

September 9th

|

September 10th

|

September 11th

|

Aided by confusion on the French part as the responsibility of holding Legnago was transferred to Sahuguet from Kilmaine, who desperately wanted the troops there for the defence of Verona, the Austrians suceeded in capturing Legnago with its bridge intact. The way to Mantua was open if Wurmser could shake off the pursuing Messena and Augereau, and either overwhelm or evade the blockading force under Sahuguet.

Note that contrary to what is shown on the map, at least part of the detachment sent ahead to secure Legnago crossed to the west side of the Adige and encountered and forced back a French force that had been sent to secure the place. Martin Brown-Boycott glosses over the details but there's a long paragraph detailing it in the narrative to map 19 in the West Point Atlas. Adlow has the most detailed accounts but his precise sources are unclear. Some accounts are available in French primary sources but are confusing. It is certain that Bonaparte was convinced the French commanders on the ground had shown insufficent backbone and presence of mind, but also that he'd placed them in a very confusing and dangerous situation. A batallion against at least 12,000 men, Wurmser's whole army in effect, even in a fortified location, had some genuine reason for concern.

In any event the capture of Legnago with its bridge intact was a coup for the Austrians, and a severe set back for the French.

Map Showing situation September 11th 1796

By the 10th of September Wurmser had reached Legnago where he paused to rest his troops. On the same day Augereau reached Este on the road from Padua and Massena the Adige near Arcole and Ronco, having marched from Vicenza via Montebello.

Massena was ordered to cut Wurmser's retreat off at Sanguinetto while Augereau pursued him from the east. Sahuguet with Kilmaine was to provide a backstop along the line of of the Molinella River which runs roughly from Roverbella to Castel d'Ario and from there between Villeimpenta and Roncoferraro south. His main position was at Castel d'Ario from which he pushed outposts forward as far as the Tione River, but he posted detachments at Duc Castelli, Begarello, Villeimpenta, and Roncoferraro as warning posts and to delay any Austrian efforts.

In the event Massena was very slow crossing the Adige at Ronco during the the night of the 10th and 11th due to a lack of boats. Wurmser marched on the morning of the 11th leaving a garrison of 1,600 to hold Legnago. Massena's troops in the meantime had by accident taken the slow river road via Angiari from Ronco. Massena's advance guard under Pijon and Murat encountered Wurmser's under Ott at the village of Cerea. A to and fro battle resulted. First Ott took the village back from the French, than Victor arrived and took it back. Then the reinforced Austrians re-took it a second time in the afternoon. The Austrians captured 736 frenchmen and almost Bonaparte according to some accounts. It's not a battle that gets prominence in French accounts.

The upshot was that by late in the night of the 11th Wurmser had reached Nogara a major town near the Tartaro River half way to Mantua from Legnago. He had Massena on his flank, Augereau behind him (though delayed by Legnago) and Sahuguet in front of him.

Finding strong French resistance in front of him at Castel d'Ario along the main road to Mantua Wurmser took a route volunteered by a local who'd come forward. He marched at midnight for Villimpenta south-west of Nogara on the Tione where he overwhelmed the weak French outposts. Shortly afterwards he crossed the Molinella between Villimpenta and Roncoferraro and was from there able to reach Mantua unimpeded.

Evening September 11th

|

September 12th

|

September 14th

|

September 15th

|

Map Showing situation September 15th 1796

Cooped up in Mantua the Austrians had too many men for their stored supplies to sustain, and more than they needed to defend the fortress. Wurmser collected his forces and attempted to meet and defeat the French outside of Mantua in the area to its north west between La Favorita and San Giorgio. At the very least this forced the French to abandon their blockading positions which allowed the Austrians to forage in the area south of Mantua called the Serreglio.

Having arrived at Mantua on the 12th, Wurmser attacked on the 13th forcing Sahuguet back to the north. On the 14th Massena's division arrived and attacked Wurmser unsucessfully.

The 15th saw the arrival of Augereau and a full out battle between the gathered forces of both sides. First Sahuguet attacked around La Favorita on the Austrians left flank to the north, then Augereau attacked around San Giorgio on the Austrians southern right flank. Finally Massena attacked in the center that had been weakened by reinforcements to the flanks, forcing it back and deciding the battle in the French favor.

So Wurmser's second attempt to relieve Mantua failed largely due to the incredible speed with which French troops marched compared to previous standards. Not expecting this Wurmser simply miscalculated the situation. It's notable that after Bassano he seems to have learned both how to force his own troops to move faster and what to expect of the French. A second advantage often ignored that the French had was their ability to quickly overrun blocking positions in mountainous terrain. This was already commented on above.

Bonaparte, of course, deserves credit for making decisive use of these advantages. His defeat of Wurmser's second advance was even more decisive than that of the first Castiglione campaign. Bonaparte too could learn.

It was not a completely unqualified French victory though. Not only had Wurmser managed to throw more fresher troops into Mantua, he'd forced the blockade to be largely lifted to the south. It would take most of the next month to quell revolts and completely restore the blockade. Even with more mouths to feed the Austians managed to gather supplies sufficent to allow them to hold out into January or February of the next year.

Wurmser's effort had bought time sufficent for further relief attempts to be made.

Note: You will need to cut and paste addresses given into your browser's address line in order to follow them.

If you have some french and a lot of patience the correspondance of Napoleon Vol I will be of interest. As of 2017-10-18 a version online can be found at https://archive.org/details/correspondancede01napouoft

Towards the end of writing this post I procured a copy of Phillip R. Cuccia's "Napoleon in Italy, The seiges of Mantua, 1796-1799". Published by the University of Oklahoma Press (www.oupress.com) in 2014, ISBNs for hardcover, mobi, and epub editions respectively 978-0-8061-4445-0, 978-0-8061-4532-7, 978-0-8061-4533-4. He provides just a gloss on the battles of manuever that took place at the time, but is very good on the seiges of Mantua particularily on the details of what units were involved. In fact his archival work provides details of the composition of various commands not present in most other secondary works. You might need to check his notes for some of these. He also buries some very good biographical detail in those notes. His maps are also outstanding and I wish I'd had them earlier as they include details I had some difficulty figuring out on my own.

Some of the spelling of placenames in Bonaparte's correspondance does not match what you'll find on a modern map in English or Italian. For instance:

This variance in spelling matters because many placenames are very similar. In fact some are exactly the same (multiple Pradellas, Rivaltas, Ospedallettos, Gazzos, etc) and can only be understood in context or by long winded elaboration. Many names are used in a shortened form, that is "Desenzaro" for "Desenzaro del Garda", "Peschiera" for "Peschiera del Garda", "Vallegio" for "Vallegio sul Mincio", "Rivoli" for "Rivoli Veronese", "Castiglione" for "Castiglione delle Stiviere", and so on.

There is also some variation in the names of people

I found it difficult to place the river Molinella near Castel d'Ario that Bonaparte orders Sahuguet to break bridges on at least according to the account he gave the Directory. The river to the east of Castel d'Ario that's the most clearly marked on most maps is called the "Tione" or sometimes on modern maps "Tonne". The river Tartaro runs parallel to it just a little further to the east. They both rise near Villafranca. The Tione runs by the villages of Nogarole, Trevenzuelo, Erbe, Sorga, Castel d'Ario, Villaimpenta, and Chiusone. The Tartaro runs by the villages of Povegliano, Vigasio, Isola-della-Scala, Pellegrina, Nogara, and Gazzo.

Further looking online took me to "mapquest.com" which does show a "Canale Molinella" that starts south of Roverbella, runs north and around Castiglione Mantovano, then to the north-east of Canedole, south of Castel Belforte, through Bigarello, and then through the northern part of the modern town of Castel d'Ario, but just south of the castle ruins there. It roughly parallels to the north the direct road (SP249 then SP10) from Roverbello to Castel d'Ario. At Castel d'Ario it bends south around the east of the town and passes between Ronco Ferraro and Villimpenta, before reaching the Canale Bianca. The whole mess gives the strong feeling of a hydrology that's been considerably altered by man. It appears this started as early as at least the 15th century so I'm afraid I have no real idea of what the exact topography was in 1796.

Another feature I'm uncertain of is Duc Castelli. It's mentioned in Bonaparte's correspondance. It appears to have been a location on the road between Roverbella and Castel d'Ario lying just south of Castel Belforte. " A sud et pres de Castel-Belforte " according to a footnote to #996 of Napoleon's correspondance on page 613 of edition referenced above. So far I've been unable to find it on any modern map.

The italian wiki page for Castel Belforte at https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Castelbelforte appears to say that in earlier times the town now known as Castel Belforte was called "Due Castelli" or "Two Castles", as opposed to the "Dukes's Castle" of "Duc Castelli". Whether this means that "Duc Castelli" is a corruption of "Due Castelli" or that these two castles were close by I do not know.

Regards Duc Castelli and other difficult locations turns out the digital collections of the New York Public library includes some useful maps.

See https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6d1df996-97eb-f6b6-e040-e00a18063a3f which accessed on 2017-12-27 as an example.

Philip Cuccia's book on the seiges of Mantua, which I only read after mostly finishing this post, has both Duc Castelli and the Molinella marked on its maps, but I rather suspect from the inspection of satellite pictures that that river has been placed somewhat south of its actual course. As much altered as the flow of water may have been the alteration of boundaries and property lines is a serious and difficult matter (note provincial boundaries seem to follow old river courses) and these suggest the river takes the course I detailed above.

Pinvenzano, 15 Fructidor, year 4 [September 1, 1796]

The bad weather which we have had for some days has obliged General Pigeon to order down the posts from Monte Baldo. If the weather changes, I shall direct him to send them up again.

The soldiers suffer cruelly: two-thirds of my division, at least, are in want of coats, waistcoats, breeches, shirts, &c., and absolutely barefoot. This deficency of clothing gives us a great many sick, and will give us a great many more, if people never do anything but promise without sending us necessaries.

I give you notice, general, that, if the movement of the general-in-chief takes place, the soldiers whom I command cannot march in any way whatever; it is physically impossible, unless one would choose to leave half of them halfway. I have no hesitation to tell you, that if same attentions are not paid to my division as to the others, I will give in my resignation and renounce the profession. Let it not be supposed tht I am swayed by ill-humour: it is as a free man and fond of what is right that I thus express myself.

I have long been applying at Verona for flour, for the purpose of setting to work the ovens that are within reach of my division. I know not from what diabolical speculation it is that they will never send anything but bread ready baked at Verona, which, when it arrives here, is always mouldy, at least two-thirds of it. When liquids are sent to us, it is always in musty casks; and, before they are landed and delivered at the magazine, half the quantity is always gone.

I have written to the commissary; I have stationed an officer of my staff at Verona; but, for all that, things do not go on as they ought to do. If you talk to the commissaries and the agents, they tell you that a much greater quantity of provisions is sent off than is wanted for the division; but they are well aware, from the letters which I have written them, that half and more is not fit to be received. Let the general-in-chief give orders that this shall be no longer the case.

Health and fraternity

Massena