The nuts and bolts of how Revolutionary War and Napoleonic period infantry fought.

Infantry tactics saw no decisive innovation during the period from 1792 to 1815. They mostly developed trends that had already been seen earlier in the 18th century. Nevertheless, infantry truly dominated the battlefield in this period and infantry tactics and organization are the background against which the world shaking Napoleonic innovations in the operational art of war took place.

Without some grasp of the basics of infantry tactics in the period any understanding of it is bound to be fuzzy and unfocused.

As it happens unfortunately drill is inherently boring, fussy, and focused on seemingly arbritary detail. Worse it never seems to have been truly standardized. Particulars of organization and tactics changed constantly over time. Different nations had different organizations. Any overview, especially one that seeks to be clear, is going to have to simplify and leave many details and exceptions out.

So when I write that the key fact about the infantry was the inaccurate and unreliable nature of their main weapon the smooth bore flintlock musket with a socket bayonet that's an oversimpilification.

Still it is true.

The inadequecies of the musket meant that to be effective it had to be used by masses of men firing all together usually at pretty close range to their enemy.

The problem the drillmasters of the 18th and early 19th century had was getting all those men to the proper places, together, and well enough organized that they could all fire on the enemy in a co-ordinated way. To do so without losing control or cohesion, and without leaving them excessively vulnerable to either cavalry attack or artillery fire.

Keep this in mind and all the detail organizes itself into attempts to achieve these ends.

Firearms had been playing an effective role on the battlefield since the early 16th century. That is for over two hundred years prior to the period we're looking at.

The introduction of the flintlock musket with socket bayonet just a hundred years before was the key infliction point in their development.

"Apart from those few solidiers armed with rifles, all Napoleonic infanty carried a smooth-bore muzzle-loading mustket, about five feet long (not counting the bayonet) and with a bore of around 0.7 of an inch. ... None of the standard muskets of the period was particularly well designed or made. They were produced in enormous quantities and economy, not precision, was the overriding concern."

Before elaborating on the many deficiencies and weaknesses of the musket let's be clear that it was the key component in a world changing tactical system that was introduced in the 1690s. The flintlock was both more dependable than the old matchlocks and required the musketeer to take up less room. Before they'd basically had to fight in open order. The flintlock meant they could be crowded into tighter formations. Formations that could generate more firepower for the space they took up.

In conjunction with the tighter formations the development of the socket bayonet that permitted a musketeer to both fire his weapon and have a bayonet mounted on the end of it meant that formations of men armed with the weapon could defend themselves against cavalry. Previously they'd needed pikemen on the field to perform that function.

"By 1700, when the socket bayonet became universal, a sucessful frontal cavalry charge against formed infantry had become impossible. The cavalry had to face volleys from a formation made up completely of musketeers and, if they still could close with the infantry, then confronted a formation entirely composed of pikemen. "

The new muskets although much more reliable than the old muskets were still, even in perfect conditions, prone to misfiring. "[I]nitially firing two-thirds of the time as the against the matchlock's 50 percent rate. Subsequent improvements enabled the musket to fire 85 percent of the time. "

"The smoothbore musket remained inaccurate. The burning of the black powder caused the barrel to foul, and to avoid having to clean the barrel during battle, the ball had a very loose fit ".

Tests under perfect parade ground conditions showed at best half of the shots from a musket hitting a large target at 100 yards. Calculations of how many shots actually fired in anger in fact managed to kill or wound someone suggest a rate of less than two percent, often much less than that, less than half a percent in most cases.

Because of the fouling problem, the wearing out of flints, the overheating of barrels, the shrouding of the battlefield in black powder smoke, and the pyschological toll on the soldier of ongoing combat, the first shot he fired was the most effective.

In any event as the individual musketman was not dependably effective the solution was to have them fire volleys in mass, and especially in the early 18th century hold off firing their first volley until the enemy was very close. Closer than 100 yards and often 50 yards or closer.

Before continuing on with how tactics by mustket armed infantrymen developed over the eighteenth century it'll be helpful to define some organizational terms.

The battalion was the main tactical unit in all western armies in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It was divided into companies for administrative purposes.

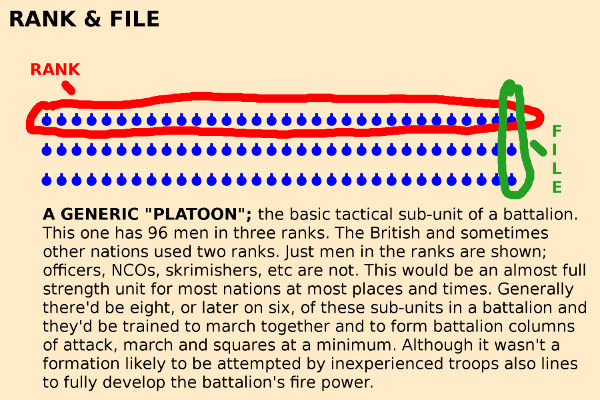

For tactical purposes battalions were often divided into different units most commonly called platoons. As in French and British usage most battalions had the same number of companies as platoons this distinction tends to be blurred by writers in English writing about battles from an English or French perspective. In Austrian, Prussian, or Russian usage it is, however, important to remember.

Battalions at full strength ran somewhere between 500 and 1200 men, and had anywhere from four to ten companies of somewhere between 80 and 200 men each. Battalions could be attritted down to only two hundred men but became ineffective at strengths under that.

The main tactical divisions of a battalion varied some what less than the number of companies usually being either eight or six in number whether they were called platoons or something else.

Although early on English and French battalions in particular might have ten or nine companies, some of these were elite grenadier or light companies and often either detached for duty elsewhere or deployed as skirmishers and were therefore not usually available when forming battalion formations.

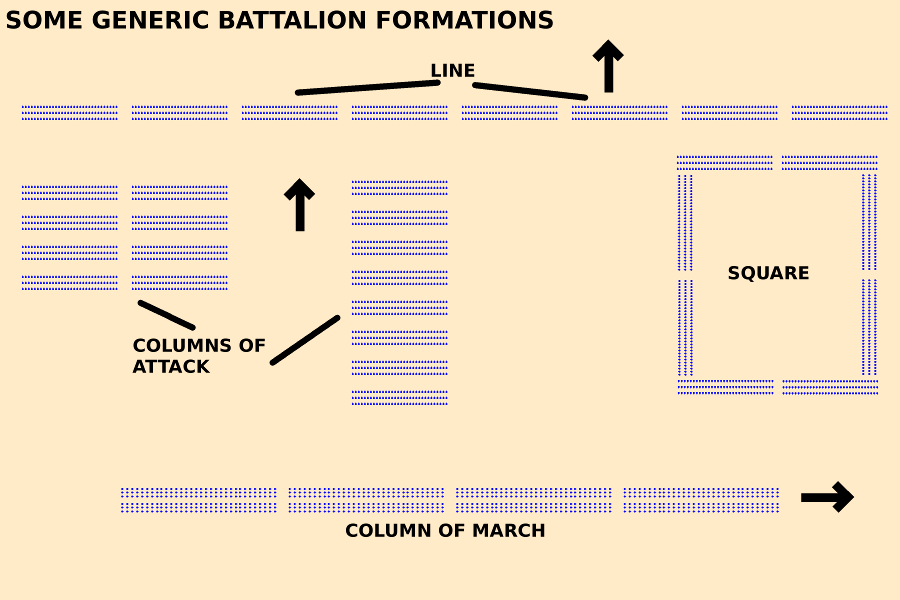

Officers, NCOs, skirmishers, etc not shown. Separations not exact. Attack columns closed up. Separations in Square exaggerated so that component sub-units can be discerned. Eight tactical sub-units by whatever name were common but this was not an invariable rule. Sub-units at almost a hundred men are on the larger side of what would be common. The British would be in two ranks so their sub-units would be longer and thinner. Each man would take up about two feet ( or one pace or about two-thirds of a yard or meter) square, so sub-units are about 22 by 4 yards in size.

The eighteenth century began with a decade and a half of general warfare. The War of the Spanish Succession was the biggest and most general conflict. It was the continuation of a generation long effort to contain the ambitions of France under Louix XIV.

It was the war that saw the introduction of the flintlock and bayonet.

Formations were primarily linear to develop the most firepower and tactics amounted to both sides lining up across from each other and closing to very near range before firing their first devastating volley.

The awkwardness of maneuvering in long thin lines meant battle was basically by mutual agreement. It was an age of seige warfare.

A premimum was placed on drill and disciple. It took well trained troops with good morale to maneuver like this and to withhold fire, perhaps while under fire themselves, until the last moment.

On the continent, either because generals recognized the drawbacks of this approach, or because it was inherently unsustainable killing sometimes thirty to fifty per cent of the well trained troops with high morale it needed with each engagement, this approach fell out of favor as the century progressed.

Only the British maintained the bloody minded discipline to routinely hold their fire until the last moment and fire their first volley at murderously close range. They did so right through mid-century and up until Waterloo at the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

After the War of Spanish Succession peace broke out in Europe for better than two decades.

Frederick the Great's father, the Soldier King, built up the Prussian army in this period. He made Prussia a military state with the best drilled army in Europe.

When Frederick took his father's army to war with Austria in 1740 its superior quality of drill provided two advantages.

One it could deploy into line faster and more efficiently than its opponents. Ideally it could be ready to fight before them and catch them at some sort of disadvantage.

Two once engaged it fired faster. The Prussian units were trained to fire more volleys in a given time than other troops.

These advantages and Frederick's operational genius allowed Prussia to defeat the larger Austrian state and its Allies.

Prussia became a Great Power.

Its army and military tactics became a model for all of Europe.

By the mid-eighteenth century the Austrians, the main opponents of the Prussians, had got the message that they needed to up their military game loud and clear.

Better drill, going by the Prussian example, appeared the way to achieve both better battlefield maneuverablity and increased firepower.

Amazingly prior to the mid-century there wasn't any standardized drill for the Austrian army overall. (This in fact seems to have been generally true for all the European powers.) Armies still had some of the private public enterprise flavor of the previous century. Regimental and battlion officers were responsible for training and drilling their troops and did so by their own lights as best they could without undue influence from higher up in the command hierarchy. The command hierarchy wasn't in fact fixed or permenant in any case.

Be that as it may as Duffy writes "Maria Theresa proclaimed to the army in 1749 'How it has come to Our notice that Our Imperial infantry posssesses neither a uniform drill, nor any uniform observation of military practice. These two shortcomings not only give rise to various disorders, but promote dangerous, harmful and damaging situations both in the field and in garrison.' In the first ten years of the reign the army had certainly gone about the business of fighting in a great variety of ways, which owed something to sets of private and public regulations, but probably rather more to the whim of individual colonels. "

Detailed regulations promulgated in 1749 laid down the basic practices of the Austrian army for the next century.

There were some changes. In 1757 soldiers went to from being arrayed in four ranks to being in three ranks. The infamous year of 1805 saw further changes at least attempted, such as using the third rank as skirmishers and faster marching paces.

Overall the 1749 regulations prevailed in theory if not always practice. In particular "[t]he battalion was divided into the sixteen tactical blocks of the little Austrian platoon, each seven or eight files wide (ten for the grenadiers). For all evolutions, however, the platoons were combined two-by-two in half divisions (each the rough equivalent of the large Prussian platoon), or in full divisions or companies of four platoons each."

In practice the favored formation seems to have been the same as in most other armies a "divisional column" this being essentially eight tactical sub-units (two platoons, a half-division, a company, or whatever) arrayed two wide and four deep. See the "column of attack" on the left in the diagram above.

This emphasis on rigourous drill seems to have come at some expense. It appears to have discouraged initiative among the troops and lower officer ranks both. It also emphasized firing volleys rapidly at the expense of the effectiveness of fire by both the individual soldier and the individual volley.

All the continental armies seem to have copied the Prussians as the Austrians did and with a similar effect. Actions tended to disintegrate into ineffectual free form fire fights before opposing units got into short enough range to inflict decisive damage.

Although line infantry in formations dominated stand up fights in Europe proper in irregular warfare both in America and on the frontiers with the Turks they proved vulnerable to harrassment by small groups of warriors using hit and run tactics.

The British responded to the drubbing Braddock got in the French and Indian War and their experience in the American Revolution with specialized riflemen. These elite troops operated in open order using the slower firing but more accurate and slightly longer ranged rifle.

The German and Austrian equivalents were called "jagers", hunters, and not always armed with rifles but expected to show individual initiative and to operate in open order both to screen their own line infantry and artillery and to harass the enemy. Practice often fell short of theory.

The use of light troops in skirmish order went from something of a side show corner case to something of decisive importance with the coming of the French Revolution.

The mass levys of Revolutionary France resulted in large numbers of units with troops who were totally untrained in drill, and who in fact were initially adverse to the discipline it required, but who were enthusiastic and often showed considerable initiative.

Of necessity they were deployed as skirmishers. What the French called chasseurs (hunters) or tirailleurs (sharpshooters).

But that's to get a little ahead of our story. France particpated both in the War of Austrian Succession and the Seven Years War around mid-century. They changed sides between one war and the next but their military performance in neither was very good. This insult to French pride led to much soul searching, debate and writing on military affairs. Some limited reforms of the Austrian sort also.

So when the Revolution came and swept away the opposition to new things the French had ideas prepared to put into practice.

The most significant of these ideas was that of a permenant structure of all arms units above the regimental level, the Corps system, something have written about elsewhere but which is not the topic of this post. Almost as significant was the concept of using columns to facilatate battlefield maneuverability. Theorists admitted the line provided better firepower but advocated that deployment into it be delayed until the last possible moment before engagement. That is if it was to be used at all.

The French theorists also pioneered the idea of all arms tactics. The line put out more fire, and the column was more maneuverable, but light troops could wear down formations, if they were tight artillery could decimate them. Cavalry was superior not only for scouting but for breaking shaken disordered troops and pursuing them once they'd broken.

The Revolution saw theory meet a lot of reality.

And the main reality was that although the artillery remained professional, and there was a leavening of formerly royalist infantry officers and units, two thirds or more of the French armies consisted of untrained masses of untrained men adverse to discipline under largely elected non-professional officers.

For the lack of any choice, and with failure not being an option for anyone that wanted to keep their heads, the officers of the new French armies deployed most of their troops in large loose clouds of skirmishers. They stiffened these with the lesser numbers of trained units they had.

Given the fragile morale of their troops and the political demands for results they favored the attack. Claims that the French national character favor the attack over defense are hard to evaluate but maybe its a revealing fact that they this became a sort of received wisdom.

These French attacks took the form of enemy formations being ground down by the plentiful skirmishers and the still professionial artillery until cracks started to appear in their morale and order. At that point additional units would be rushed in in column and press home violent attacks against the wavering and usually locally outnumbered enemy formations.

It was a wasteful and irregular form of warfare but more and more frequently the French officer corps learned how to make it work.

The soldiers learned also. It's interesting that even after their successes in early 1796 that units in Bonaparte's Army of Italy were eager to learn the drills that would enable them to assume formations that would both enable them to deploy to effect on the battlefield and to defend themselves against enemy cavalry.

Years of bitter experience taught the survivors of the Revolutionary armies the advantages of being professional. Winning was much better than defeat or even stalemate. If it took drill and discipline to achieve that then so be it.

The end of the Revolutionary Wars saw the theories of pre-revolutonary theorists finally being put into effect by seasoned veteran troops and officers.

The years of peace prior to 1805 and the commencement of the Napoleonic Wars saw the French Army reach its acme with as the Grande Armee, full of veterans, received several years of training at all levels from the company to the Corps.

The Army that won at Austerlitz , Jena, and Auerstedt was both experienced and superbly trained.

The wars in Poland and Spain began to wear it down. The year of 1808 saw simplications made to the standard organization and drill of the French Army. The renewal of war in 1809 saw a further deterioration resulting in clumsy mass formations such as that used at Wagram .

The allies had certainly upped their game, but the French had also fallen off theirs.

The 1812 campaign against Russian completed the destruction of the old Grande Armee.

The 1813 campaign in Germany and 1814 campaign in France were fought by often enthusiastic, but usually very inexperenced troops, something that cost them horribly.

The 1815 French army was smaller but full of trained veterans. Arguably it was misused by an officer corps that wasn't was it had been anymore. In any event it proved brittle winning at Ligny , but not holding up after Waterloo.

To sum up the state of tactics in the French army wasn't a constant. In any year other than 1805 different units might have a very different level of proficiency. The average levels of experience and training varied drastically depending on the year.

Very poor from 1793 to 1796, but rapidly improving after that until 1801.

Very good in 1805 and 1806.

Going downhill from 1807 until 1813 at least. At least somewhat better at the end when the army was smaller but mostly consisted of experienced veterans.

Formal organization did not change so much.

For most of the period as Griffiths writes "[i]n theory each battalion should have 8 platoons (or 9, if we include the grenadier platoon that was often detached), each of 114 men, making a total of 912 (or 1,026)."

In the last part of the Napoleonic period new regulations were promulagated and this was modified. As Griffiths goes on to write: "[i]n early 1808 this was changed to 6 platoons of each of 140 men, including one of grenadiers and voltigeurs, making a total of 840."

Note that voltigeurs (leapers) was another name for light infantry. In theory they were elite specialists, in practise most often just generic light infantry. Also of course in practise the size of battalions and their sub-units was much smaller than full strength.

Up until the February 1808 reforms the nominal manual of arms was the Guibert inspired Reglement of 1791. It provided for the standard menu of battalion formations, line, square, and various sorts of square, along with instructions on how to change from one formation to another. As mentioned the line provided the most firepower but wasn't maneuverable, the square was defense against cavalry but vulnerable to artillery, and the various columns provided various degrees of maneuverabilty along with various degress of firepower and protection against cavalry.

Apparently there wasn't much prescribed for light infantary. In the field especially with the semi-trained troops that prevailed at most times the preferred formation was the wide column of attack.

This wide "divisional battalion column", "divison" in this case meaning two companies not the all arms higher level formation of two regiments, was usually two companies wide and four deep up until 1808 when it became only three deep. Once again note that in French (as well as British) usage a company and platoon were functionally the same.

Also note the next formation troops would be taught was the square so they'd have some hope against cavalry. The wide column of attack being awkward except on open ground or very wide roadways the troops of necessity have to be trained to change into columns of march so they could march along narrower roads and through contricted spaces (defiles). Only once these evolutions were mastered did it make sense to train troops how to form up in the lines as was in theory tactically superior.

Developments with the Austrians paralleled and coverged with those on the part of the French they spent so much time fighting.

Starting with an army well drilled in the linear tactics of the mid-eighteenth century they had to change to deal with the more flexible French. They had to answer the increased French use of light skirmishers. Also despite taking heavy losses in the last years of the eighteenth century and the first ones of the nineteenth they tried to expand their numbers to match the French ones. This necessarily led to a dilution of well trained troops by much less experienced ones.

As with the French what was theorectically desirable had to give way to what was practically possible with the troops they had.

Despite attempted reform in 1801, 1805, and 1807 by the Archduke Charles and General Mack among others in practise the tactical organization and basic drill of the Army remained that of 1749.

Increased used of attack columns as "masses" was attempted in the later Napoleonic era.

A sort of impromptu solid square to defend against cavalry was developed. Instead of performing elaborate evolutions in which the half companies (the platoons of other armies) moved to form a hollow square instead troops in an attack column (two wide and four deep) would completely close up the two forward sub-units would remain facing forwards and outwards. The middle sub-units would do right turns to face outward, and the two sub-units at the back would do about faces (180 turns) to face backwards and out.

This form of solid battalion square didn't have a hollow for other troops and officers to shelter in, and it sacrificed the firepower of the men in its interior but it was quick and easy to form.

The British Army remained much more a traditional professional eighteenth century army, and thus more attached to linear tactics, than the continental armies.

There were reforms. Famously Sir John Moore attempted to improve both the treatment and morale of British troops. He also spurred the development of light troops which were embodied in the 95th Rifle Regiment and Crauford's Light Division. The riflemen were to prove an important counter to French skirmishers in the Peninsula.

Organizationally the British battalion usually had ten companies, one grenadier, one light and eight regular. As the Grenadiers were often detached and the Light infantry deployed as skirmishers, and in British usage platoons corresponded in practise to companes, this means they had the usual eight battalion tactical sub-units that most powers did.

The tactical manual used throughout was that developed by Sir David Dundas which had a total of eighteen maneuvers specified. Haythornthwaite reproduces them very usefully in his Elite #164 Osprey book on the topic. (See below for bibliographical details.)

As Haythornthwaite writes "[i]n the period preceding the commencement of the French Revolutionary Wars the British infantry had no unified system of drill, so that 'every commanding officier maneouvered his regiment after his own fashion'".

Dundas published his Manual of Military Movements in 1788 and in 1792 General William Fawcett "ordered that an amended version should be issued officially".

Actual application was hit and miss, and in particular, by 1800 most British units had gone to using two ranks instead of three as advocated by Dundas based on Prussian experience.

Nosworthy writes at length on how the British Army only semi-formally developed a tactical system based on shared experience and the fact they had mostly well trained professional troops.

In particular the British units had several years of peacetime drill together in Britain prior to being deployed to the Peninsula.

These was the basis upon which Wellington built his tactical system for defeating the French system that had proved so successful in the rest of Europe.

Wellington coldly analysed the French system and determined both its strengths and its weaknesses.

The French fully understood the theoretically better firepower provided by troops in line formation. However, in practise they did not rely on superior firepower on the part of line troops.

In practise the French accepted that fights between opposing line units tended to become bogged down in extended fire fights at ranges too great to achieve decisive results.

The French allowed their artillery and skirmishers to weaken enemy formations. They then moved up the line infantry to take advantage. They tried to use the superior maneuverability of their columns to get superior numbers and take their opponents at a rush but if the first units became bogged down and a position was critical they'd quickly move up fresh units to try and tip the fight.

This worked often enough to grant the French victories throughout Europe.

Wellington thought it a false system and developed counters to each part. In particular he kept protected his line infantry from both artillery and skirmisher harassment using a combination of deploying in depth, on reverse slopes, and behind thick screens of his own light infantrymen.

He was careful to ensure that once the French committed their line infantry that it should be quickly and decisively defeated. The British troops would withhold their fire until a single devestating first volley could be fired and generally that would be followed by a bayonet charge that would repel the French attack and prevent a general firefight from developing.

This often took the form of a surprised French column meeting a British unit formed in line on a reverse slope. Hence the long line versus column debate.

It was a system that required careful control of the battlefield using well trained troops. Where that precondition was met it worked well.

The Russians in form were quite similar to the the other European powers despite being in spirit quite different in some ways.

Formal organization varied but in practise they often had four companies in a battalion, but tactically maneuvered with eight sub-units called platoons.

Russian units were not as prone to demoralization by French demonstrations as those of other European powers. On the other hand despite being mostly made up of long serving troops the quality of their training was not great.

The formal rules of drill they used dated from 1796 and 1797 when Paul I was reigning. These were an attempt to emulate Prussian practice.

As Haythornthwaite writes in his Osprey book on the Russian army "in practice the 1796-97 Codes seem to have been less significant than the ideas of the individual commander, Suvarov theories having influenced his subordinates."

Among those subordinates was one Kutuzov who has received much of the credit for Russia's 1812 triumph over Napoleon's invasion.

In any event Suvarov believed in bayonet attacks rather than the application of firepower and as he was a very successful general and a Russian national hero those views were influential.

Their experience with the French in 1812 only exacerbated the Russian tendancy to attack in mass with battlions in wide double attack column formation rather than relying on linear formations to fully develop the firepower of their line infantry.

There is a conventional story that an out-moded eighteenth Prussian army met a new French Napoleonic army at Jena and Auerstedt in 1806 and that the conservatism of the Prussian state received its due comeuppance when that old-fashioned army was shattered and Prussian profoundly defeated.

At best this seems to be an exaggerated oversimplification.

Hofschroer makes a good case that at the tactical level that we're looking at this simply wasn't true.

The Prussian army had not completely ossified on the tactical level. It continued to track trends in the rest of Europe with an ongoing set of reforms.

On the level of the individual infantry battalion the Prussians seem to have been quite proficient. They were flexible and efficent in adopting tactical formations suitable to their circumstances and not hopelessly devoid of useful light infantry to deploy as skirmishers to counter the French ones.

At a tactical level their deficiencies seem to have been of two sorts.

One although well trained they were not experienced in actual warfare. After 1795 Prussia spent over a decade at peace.

Second the different arms, the infantry, the artillery, and the cavalry did not cooperate well. Serious issues but not exactly germane to the study of battalion level, mostly line infantry, tactics being explored in this post.

Most of all the Prussians suffered from poor strategic and operational command. Again not immediately germane to this discussion.

That the Prussian army was shattered and forciably reduced to a much smaller size is.

This produced a strong impluse to reform in Prussia that more conservative elements were unable to contain. It also meant that the newly enlarged Prussian armies of 1813 to 1815 would be mostly composed of reliatively inexperienced and untrained troops.

The greatest achievement of the Prussian Reformers was to build on French development of the Corps System, and most of all to improve and institutionalize the French staff system.

Neither specifically related to battalion level tactics.

The Prussians retained their organization of battalions into eight tactical sub-units (platoons or Zugs). They had the usual menu of formations, line, column, and square.

Even more than the Austrians they deemphasized the line and old fashioned square in favor of attack columns that could quickly switch to an outward faceing solid square if threatened by cavalry.

Theoretically this had the advantage of greater maneuverabilty on the battlefield, but one cannot help think it may have reflected the fact that their newly raised if well motivated troops of 1813 couldn't be expected to handle anything much more complicated.

Essentially the Prussians, like the Austrians and Russians but unlike the British, countered the French with a dose of their own medicine.

In the end both approaches seem to have worked well enough.

Eighteenth century and Napoleonic warfare was fought by battalions of massed musketmen who needed to fire in volleys to be effective.

The battalions were subdivided into sub-units, usually eight or six, that allowed them to assume a set of formations appropriate to different circumstances.

Lines allowed the greatest firepower but were vulnerable to flank and rear attack and not at all maneuvrable.

Columns of different dimensions allowed more maneuverabilty but developed less firepower. Columns of attack that were wider than deep were a popular compromise, increasingly so as time went by, but needed open ground. Narrower columns were adopted for more restricted ground and for marches.

When faced with cavalry some sort of square was appropriate. They tended to be vulnerable to artillery though and not very maneuverable.

Men could learn a basic proficiency in some simple formations, columns and squares, in a few months but it took them years to become truly competant. Time that was not always available in the real world.

There was constant experimentation and reform throughout the period, but the basics remained constant.

They did so right up until the mid nineteenth century and the start of significant improvements to infantry firearms with the Minie ball and rifled muskets.